Following is a basic implementation of the Xorshift RNG (copied from the Wikipedia):

uint32_t xor128(void) {

static uint32_t x = 123456789;

static uint32_t y = 362436069;

static uint32_t z = 521288629;

static uint32_t w = 88675123;

uint32_t t;

t = x ^ (x << 11);

x = y; y = z; z = w;

return w = w ^ (w >> 19) ^ (t ^ (t >> 8));

}

I understand that w is the returned value and x, y and z are the state ("memory") variables. However, I can't understand the purpose of more than one memory variable. Can anyone explain me this point?

Also, I tried to copy the above code to Python:

class R2:

def __init__(self):

self.x = x = 123456789

self.y = 362436069

self.z = 521288629

self.w = 88675123

def __call__(self):

t = self.x ^ (self.x<<11)

self.x = self.y

self.y = self.z

self.z = self.w

w = self.w

self.w = w ^ (w >> 19) ^(t ^ (t >> 8))

return self.w

Then, I have generated 100 numbers and plotted their log10 values:

r2 = R2()

x2 = [math.log10(r2()) for _ in range(100)]

plot(x2, '.g')

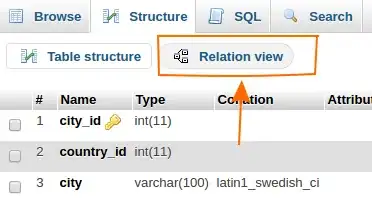

Here is the output of the plot:

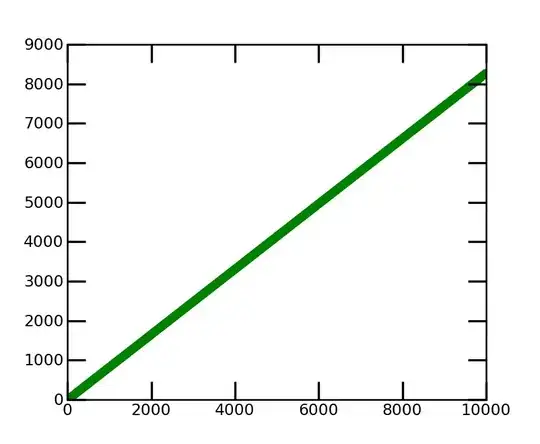

And this what happens when 10000 (and not 100) numbers are generated:

The overall tendency is very clear. And don't forget that the Y axis is log10 of the actual value.

Pretty strange behavior, don't you think?