I will focus on the definition of the first example.

The first example is defined with unspecified behavior. This means that there are multiple possible results, but the behavior is not undefined.

(And the if the code can handle those results, the behavior is defined.)

A trivial example of unspecified, behavior is:

int a = 0;

int c = a + a;

It is unspecified whether left a or right a is evaluated first, as they are unsequenced. The + operator doesn't specify any sequence points1. There are two possible orderings, either left a is evaluated first and then right a, or vice-versa. Since neither side is modified2, the behavior is defined.

Had left a or right a been modified without a sequence point, i.e. unsequenced, the behavior would be undefined2:

int a = 0;

int c = ++a + a;

Had left a or right a been modified with a sequence point in between, then the left and the right side would be indeterminately sequenced3. This means that they are sequenced, but it is unspecified which one is evaluated first. The behavior would be defined. Mind that comma operator introduces a sequence point4:

int a = 0;

int c = a + ((void)0,++a,0);

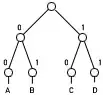

There are two possible orderings.

If left side is evaluated first, then a evaluates to 0. Then the right side is evaluated. First (void)0 is evaluated followed by a sequence point. Then a is incremented, followed by a sequence point. Then 0 is evaluated as 0 and is added to the left side. The result is 0.

If the right side is evaluated first, (void)0 is evaluated followed by a sequence point. Then a is incremented, followed by a sequence point. Then 0 is evaluated as 0. Then the left side is evaluated, and a evaluates to 1. The result is 1.

You example falls into the latter category, as the operands are indeterminately sequenced. The function call serves the same purpose5 as the comma operators in the above example. Your example is complicated, so I will use mine, which also applies to yours. The only difference is that there are many more possible results in your example that in mine, but the reasoning is the same:

void Function( int* a)

{

++(*a);

return 0;

}

int a = 0;

int c = a + Function( &a );

assert( c == 0 || c == 1 );

There are two possible orderings.

If the left side is evaluated first, a evaluates to 0. Then the right side is evaluated, there is a sequence point and the function is called. Then a is incremented, followed by another sequence point introduced by the end of the full expression6, the end of which is indicated by the semicolon. Then 0 is returned and added to 0. The result is 0.

If the right side is evaluated first, there is a sequence point and the function is called. Then a is incremented, followed by another sequence point introduced by the end of the full expression. Then 0 is returned. Then the left side is evaluated, and a evaluates to 1 and is added to 0. The result is 1.

(Quoted from: ISO/IEC 9899:201x)

1 (6.5 Expressions 3)

Except as specified

later, side effects and value computations of subexpressions are unsequenced.

2 (6.5 Expressions 2)

If a side effect on a scalar object is unsequenced relative to either a different side effect

on the same scalar object or a value computation using the value of the same scalar

object, the behavior is undefined.

3 (5.1.2.3 Program execution)

Evaluations A and B are indeterminately sequenced when A is sequenced

either before or after B, but it is unspecified which.

4 (6.5.17 Comma operator 2)

The left operand of a comma operator is evaluated as a void expression; there is a

sequence point between its evaluation and that of the right operand.

5 (6.5.2.2 Function calls 10)

There is a sequence point after the evaluations of the function designator and the actual

arguments but before the actual call.

6 (6.8 Statements and blocks 4)

There is a sequence point between the evaluation of a full expression and the

evaluation of the next full expression to be evaluated.