In libgit2 headers I read that after fetch, if fast forward is signalized to be available during analysis, then what's needed is simple checkout of the fetched tip (and altering of heads/<branch>). It seemed logical, however I wonder, how can the refs/heads/<branch> be differentiated from remotes/<remote>/<branch> ? Commits have parents embedded in them – that constitutes a single history, while there should be two histories, with additional "Merge" commits in both of them. How is fast-forward implemented then? It really leads to SHA hashes to repeat in both histories, so libgit2 seems to have its point.

2 Answers

A "fast forward" isn't a merge at all, it just sets the branch pointer to "their" side of the merge.

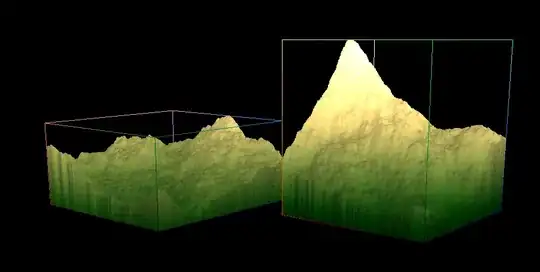

Consider some history:

1 -- 2 -- 3 -- 4 -- 5 -- 6

And consider that my master branch is at commit 4, and the server's master branch is at commit 6.

If I wish to do a merge of the parent's master branch into mine (perhaps as part of a pull), the first step of a merge is to find the merge base, or the common ancestor between those two commits.

In this case (above), 4 is the common ancestor between 4 and 6. So there are no commits locally that the server doesn't have, so you can simply "fast forward" your branch, updating its pointer to point to 6. You will not have lost any data by doing this (though you will have also not created any - if you had forced an actual merge with a "no fast forward" option then you would create a new merge commit between 4 and 6.

So libgit2's git_merge_analysis function, which identifies whether a merge can be fast-forwarded or not, literally just checks to see if the "yours" branch is your own common ancestor with the "theirs" branch.

This is, of course, not the typical merge case. Consider:

F -- G

/

A -- B -- C -- D -- E

In this case, if you are at commit G locally and the upstream is at commit E then your common ancestor is C and a fast forward is not possible, you must perform a true merge.

- 74,857

- 14

- 158

- 187

-

I agree with all and it was what I meant in post. The point is about following example case: local history with a "Merge " commit – which isn't there on remote, because the merge wasn't performed there – only local branch had to do merge, in second situation that you've described. Now, if I do a following fast forward – fetch say 2 new commits from the remote and set heads/

to the new tip – I will basically switch my local branch into remote tracking branch remotes/ – Rob Luca Aug 12 '16 at 11:23/ . That remote tracking branch does not have my previous local "Merge" commit. -

@RobLuca Why would you want to do a fast-forward merge in that case? The merge analysis should _not_ suggest that you do a fast-forward here. – Edward Thomson Aug 12 '16 at 11:40

-

OK but in general, if I at any moment set branch head at remotes/

/ – Rob Luca Aug 12 '16 at 13:07, even later when fast-forward will be available, then I will constitute single history. It apparently seems that *local* "Merge" commits are pushed back to remote, and remote's "Merge" commits are pulled to local, and there really is a single history.

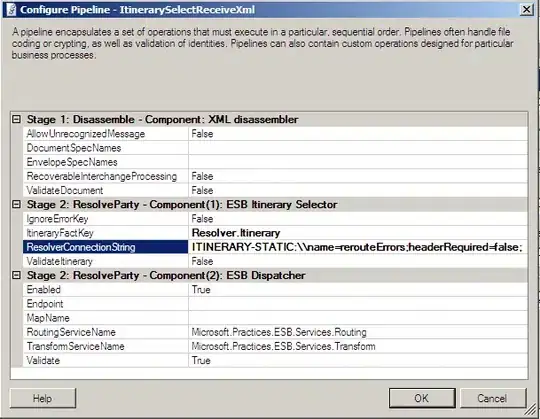

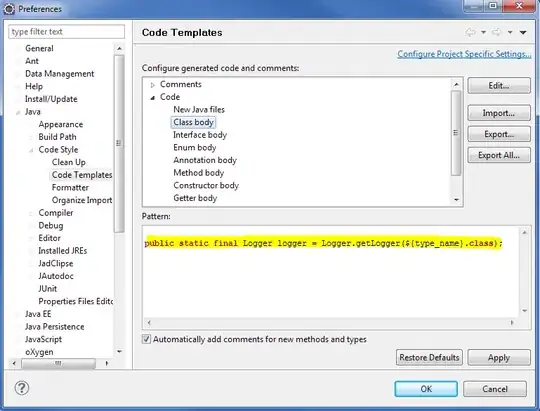

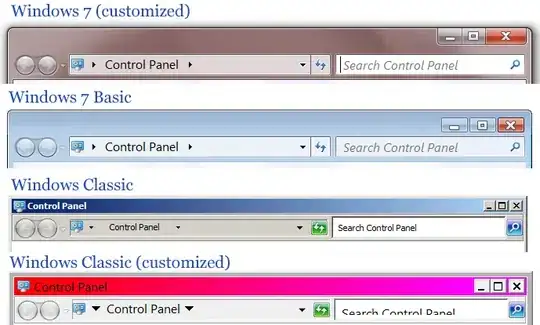

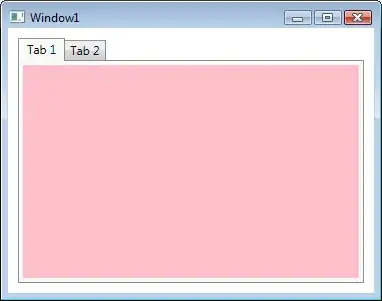

Since Git is a CVCS, the local repo and the remote one can be considered logically as one repo. refs/heads/master(r) is refs/heads/master in the remote repo.

The remote master has been updated by others.

Now we want to update the local master with the remote master via git pull origin master.

First git fetch origin master is run internally and remotes/origin/master is updated. This is actually a fast-forward merge. remotes/origin/master moves from C to E.

And then git merge remotes/origin/master is run. refs/heads/master is updated via a fast-forward merge. It moves from C to E too.

If refs/heads/master was updated by us before the pull, it would be a true merge instead. Before the pull it was like

Here we have two options, git pull origin master or git pull origin --rebase master.

The fetch process is the same.

Without --rebase, it would be a true merge.

With --rebase, it would be a rebase.

P could be just ignored now since it's not referred to by any branch or tag now.

Taking the last case for example, if we now push refs/heads/master to the remote, refs/heads/master(r) would be updated by a fast-forward merge in the remote repo.

- 27,194

- 6

- 32

- 53

-

The "Without --rebase, it would be a true merge." shows (M) commit that is for both local and remote repos. This would explain how having different merge situations (merging local with remote isn't the same as merging the remote with local – histories, the merge commits in them, will be different) doesn't lead to two histories – merge commits are pushed to the remote. Correct? – Rob Luca Aug 12 '16 at 15:23

-

@RobLuca we may have different understanding about what commits and branches are. Though `remotes/origin/master` may be called a remote branch, it's a branch in the local repo. In fact, we cannot merge `refs/heads/master` to `remotes/origin/master` because we cannot check out `remotes/origin/master` directly. Considering two branches `Ba` and `Bb`, if and only if `Ba` is an ancestor of `Bb`, we can make a fast-forward merge from `Bb` to `Ba`, simply moving `Ba` from the previous commit to the commit that `Bb` points to. – ElpieKay Aug 12 '16 at 15:47