As far as I am concerned, keeping a linear history is mostly for asthetics. It's a very good way for a very skilled, disciplined developer to tidy up the history and make it nice to skim through. In a perfect world, we should have a perfectly linear history that makes everything crystal clear.

However, on a large team in an enterprise environment I often do not recommend artificially keeping a linear history. Keeping history linear on a team of sharp, experienced, and disciplined developers is a nice idea, but I often see this prescribed as a 'best practice' or some kind of 'must do'. I disagree with such notions, as the world is not perfect, and there are a lot of costs to keeping a linear history that people do not do a good job of disclosing. Here's the bullet list overview:

- Rewriting history can include erasing history

- Not everybody can even rebase

- The benefits are often overstated

Now, let's dig into that. Warning: Long, anecdotal, mostly ranting

Rewriting history can include erasing history

Here's the problem with rebasing all of your commits to keep everything nice and linear: Rebasing is not generally loss-less. There is information- real, actual things that were done by the developer - that may be compressed out of your history when you rebase. Sometimes, that's a good thing. If a developer catches their own mistake, it's nice for them to do an interactive rebase to tidy that up. Caught-and-fixed mistakes have already been handled: we don't need a history of them. But some people work with that one individual who always seems to screw up merge conflicts. I don't personally know any developers named Neal, so let's say it's a guy named Neal. Neal is working on some really tricky accounts receivable code on a feature branch. The code Neal wrote on his branch is 100% correct and works exactly the way we want it to. Neal gets his code all ready to get merged into master, only to find there are merge conflicts now. If Neal merges master into his feature branch, we have a history of what his code originally was, plus what his code looked like after resolving the merge conflicts. If Neal does a rebase, we only have his code after the rebase. If Neal makes a mistake when resolving merge conflicts, it will be a lot easier to troubleshoot the the former than it will be the latter. But worse, if Neal screws up his rebase in a sufficiently unfortunate way (maybe he did a git checkout --ours, but he forgot he had important changes in that file), we could altogether lose portions of his code forever.

I get it, I get it. His unit tests should have caught the mistake. The code reviewer should have caught the mistake. QA should have caught the mistake. He shouldn't have messed up resolving the merge conflicts in the first place. Blah, blah, don't care. Neal is retired, the CFO is pissed because our ledger is all screwed up, and telling the CFO 'according to our development philosophy this shouldn't have happened' is going to get me punched in the face.

Not everybody can even rebase, bro. Yes, I've heard: You work at some space age startup, and your IoT coffee table uses only the coolest and most modern, reactive, block-chain based recurrent neural network, and the tech stack is sick! Your lead developer was literally there when Go was invented, and everybody who works there has been a Linux kernel contributor since they were 11. I'd love to hear more, but I just don't have time with how often I'm being asked 'How do I exit git diff???'. Every time someone tries to rebase to resolve their conflicts with master, I get asked 'why does it say my file is their file', or 'WHY DO I ONLY SEE PART OF MY CHANGE', and yet most developers can handle merging master into their branch without incident. Maybe that shouldn't be the case, but it is. When you have junior devs and interns, busy people, and people who didn't find out what source control is until they had already been a programmer for 35 years on your team, it takes a lot of work to keep the history pristine.

The benefits are often overstated.

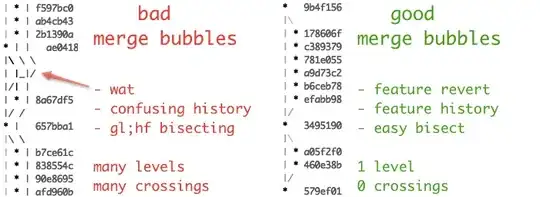

We've all been on that one project where you do git log --graph --pretty and suddenly your terminal has been taken over by rainbow spaghetti. But history is not hard to read because it's non-linear...It's hard to read because it's sloppy. A sloppy linear history where every commit message is "." is not going to be easier to read than a relatively clean non-linear history with thoughtful commit messages. Having a non-linear history does not mean you have to have branches being merged back and forth with each other several times before reaching master. It does not mean that your branches have to live for 6 months. An occasional branch on your history graph is not the end of the world.

I also don't think doing a git bisect is that much more difficult with non-linear history. A skilled developer should be able to think of plenty of ways to get the job done. Here's one article I like with a decent example of one way to do it.

https://blog.smart.ly/2015/02/03/git-bisect-debugging-with-feature-branches/

tldr; I'm not saying rebases and linear history aren't great. I'm just saying you need to understand what you're signing up for and make an informed decision about whether or not it's right for your team. A perfectly linear history is not a necessity, and it certainly isn't free. It can definitely make life great in the right circumstances, but it will not make sense for everyone.