Suppose we have a source IEnumerable sequence:

IEnumerable<Tuple<int, int>> source = new [] {

new Tuple<int, int>(1, 2),

new Tuple<int, int>(2, 3),

new Tuple<int, int>(3, 2),

new Tuple<int, int>(5, 2),

new Tuple<int, int>(2, 0),

};

We want to apply some filters and some transformations:

IEnumerable<int> result1 = source.Where(t => (t.Item1 + t.Item2) % 2 == 0)

.Select(t => t.Item2)

.Select(i => 1 / i);

IEnumerable<int> result2 = from t in source

where (t.Item1 + t.Item2) % 2 == 0

let i = t.Item2

select 1 / i;

These two queries are equivalent, and both will throw a DivideByZeroException on the last item.

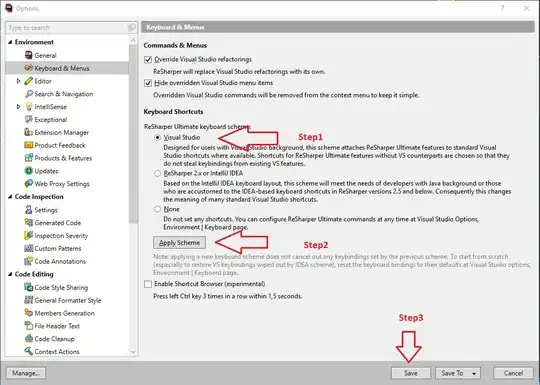

However, when the second query is enumerated, the VS debugger will let me inspect the entire query, thus very handy in determining the source of the problem.

However, there is no equivalent help when the first query is enumerated. Inspecting into the LINQ implementation yields no useful data, probably due to the binary being optimized:

Is there a way to usefully inspect the enumerable values up the "stack" of IEnumerables when not using query syntax? Query syntax is not an option because sharing code is impossible with it (ie, the transformations are non trivial and used more than once).