This specific part of the author's argument is economic. The argument seems to take roughly the following form:

- Direct resource extraction will become more difficult as we exhaust the easily-accessible and are forced to extract deeper, further away, and more dangerously

- More difficult --> more expensive

- More expensive --> we will find and use cheaper alternatives

- Using those cheaper alternatives in accordance with economic concerns will avoid problems and cause good things

I see some problems with this argument.

First, economic efficiency is a tool, not a master. It is used to produce good. It's trivial to find examples where economic efficiency produces suboptimal human outcomes. It is wrongheaded to assert that because something is economically efficient that it is therefore good.

It can therefore be argued that letting resources get rare and expensive and being economically forced to use something else is not necessarily the optimal outcome.

Second, isn't recycling one of the alternatives he thinks will naturally arise? The costs of resources are going up, not necessarily to the immediate producer or consumer, but to society. Society considers the costs and externalities of continued direct resource extraction and decides cooperatively to recycle more and extract less. I fail to see the logical fallacy.

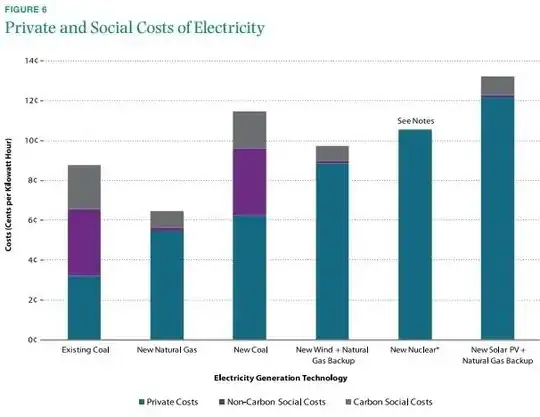

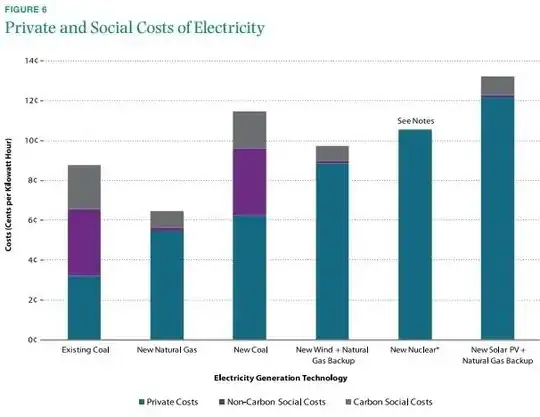

This is a great example of the pitfalls that arise from relying on economic costs to drive shifts in resource utilization. Those costs are frequently either not easily recognized by the decision-maker, or are externalized to someone else. As Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney of the Hamilton Project note in the realm of energy,

the status quo is characterized by a tilted playing field, where energy choices are based on the visible costs that appear on utility bills and at gas pumps. This system masks the “external” costs arising from those energy choices, including shorter lives, higher health care expenses, a changing climate, and weakened national security.

Their example is electricity, but the principle applies to any resource or scarce good. They quantify energy costs, including external ones:

(Image via Ezra Klein)

So purely rational economic actors, per Benjamin's model, will choose poorly due to externalized or unaccounted costs. In this way, alternative resources that are cheaper in fact might be eschewed because they appear more expensive. For example, recycling to conserve energy, land, or resources might be the most cost-effective choice, but since those costs are spread out across society (and perhaps concentrated on groups with less political power), using Benjamin's approach would cause it to remain the choice not taken.

Third, we have historical examples of cultures that run counter to his purely theoretical construction. Easter Islanders cut down every last tree, regardless of his idea that the increasing costs will spur innovation and the use of alternative resources. Theories which have counterexamples should be re-evaluated.