TL;DR: A lacto-ovo vegetarian diet does use less resources than a meat-based diet. However, neither diet is currently sustainable.

First off, this is the (very long) "recent United Nations report" PETA is referencing on their website and this is the press release for it

The press release: (emphasis mine)

Rearing cattle produces more greenhouse gases than driving cars, UN report warns

Cattle-rearing generates more global warming greenhouse gases, as measured in CO2 equivalent, than transportation, and smarter production methods, including improved animal diets to reduce enteric fermentation and consequent methane emissions, are urgently needed, according to a new United Nations report released today.

“Livestock are one of the most significant contributors to today’s most serious environmental problems,” senior UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) official Henning Steinfeld said. “Urgent action is required to remedy the situation.”

Cattle-rearing is also a major source of land and water degradation, according to the FAO report, Livestock’s Long Shadow–Environmental Issues and Options, of which Mr. Steinfeld is the senior author.

“The environmental costs per unit of livestock production must be cut by one half, just to avoid the level of damage worsening beyond its present level,” it warns.

When emissions from land use and land use change are included, the livestock sector accounts for 9 per cent of CO2 deriving from human-related activities, but produces a much larger share of even more harmful greenhouse gases. It generates 65 per cent of human-related nitrous oxide, which has 296 times the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of CO2. Most of this comes from manure.

And it accounts for respectively 37 per cent of all human-induced methane (23 times as warming as CO2), which is largely produced by the digestive system of ruminants, and 64 per cent of ammonia, which contributes significantly to acid rain.

With increased prosperity, people are consuming more meat and dairy products every year, the report notes. Global meat production is projected to more than double from 229 million tonnes in 1999/2001 to 465 million tonnes in 2050, while milk output is set to climb from 580 to 1043 million tonnes.

The global livestock sector is growing faster than any other agricultural sub-sector. It provides livelihoods to about 1.3 billion people and contributes about 40 per cent to global agricultural output. For many poor farmers in developing countries livestock are also a source of renewable energy for draft and an essential source of organic fertilizer for their crops.

Livestock now use 30 per cent of the earth’s entire land surface, mostly permanent pasture but also including 33 per cent of the global arable land used to producing feed for livestock, the report notes. As forests are cleared to create new pastures, it is a major driver of deforestation, especially in Latin America where, for example, some 70 per cent of former forests in the Amazon have been turned over to grazing.

At the same time herds cause wide-scale land degradation, with about 20 per cent of pastures considered degraded through overgrazing, compaction and erosion. This figure is even higher in the drylands where inappropriate policies and inadequate livestock management contribute to advancing desertification.

The livestock business is among the most damaging sectors to the earth’s increasingly scarce water resources, contributing among other things to water pollution from animal wastes, antibiotics and hormones, chemicals from tanneries, fertilizers and the pesticides used to spray feed crops.

Beyond improving animal diets, proposed remedies to the multiple problems include soil conservation methods together with controlled livestock exclusion from sensitive areas; setting up biogas plant initiatives to recycle manure; improving efficiency of irrigation systems; and introducing full-cost pricing for water together with taxes to discourage large-scale livestock concentration close to cities.

There was a study at Cornell, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, that looked specifically at the sustainability of meat based diets vs plant based diets. They studied lacto-ovo vegetarians (who also include eggs and milk products in their diets) not vegans though.

The lactoovovegetarian diet was selected for this analysis because most vegetarians are on this or some modified version of this diet. In addition, the American Heart Association reported that the lactoovovegetarian diet enables individuals to meet basic nutrient needs.

The study concluded the lacto-ovo vegetarian diet used less land, water and energy than its meat counterpart. Here is the abstract: (emphasis mine)

Worldwide, an estimated 2 billion people live primarily on a meat-based diet, while an estimated 4 billion live primarily on a plant-based diet. The US food production system uses about 50% of the total US land area, 80% of the fresh water, and 17% of the fossil energy used in the country. The heavy dependence on fossil energy suggests that the US food system, whether meat-based or plant-based, is not sustainable. The use of land and energy resources devoted to an average meat-based diet compared with a lactoovovegetarian (plant-based) diet is analyzed in this report. In both diets, the daily quantity of calories consumed are kept constant at about 3533 kcal per person. The meat-based food system requires more energy, land, and water resources than the lactoovovegetarian diet. In this limited sense, the lactoovovegetarian diet is more sustainable than the average American meat-based diet.

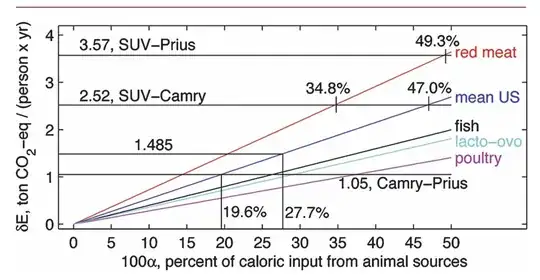

Another study, also published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition studied the environmental effects of lacto-ovo vegetarians vs meat eaters in California. It came to the same conclusion with some interesting numbers. Here is the abstract: (emphasis mine)

Food demand influences agricultural production. Modern agricultural practices have resulted in polluted soil, air, and water; eroded soil; dependence on imported oil; and loss of biodiversity. The goal of this research was to compare the environmental effect of a vegetarian and nonvegetarian diet in California in terms of agricultural production inputs, including pesticides and fertilizers, water, and energy used to produce commodities. The working assumption was that a greater number and amount of inputs were associated with a greater environmental effect. The literature supported this notion. To accomplish this goal, dietary preferences were quantified with the Adventist Health Study, and California state agricultural data were collected and applied to state commodity production statistics. These data were used to calculate different dietary consumption patterns and indexes to compare the environmental effect associated with dietary preference. Results show that, for the combined differential production of 11 food items for which consumption differs among vegetarians and nonvegetarians, the nonvegetarian diet required 2.9 times more water, 2.5 times more primary energy, 13 times more fertilizer, and 1.4 times more pesticides than did the vegetarian diet. The greatest contribution to the differences came from the consumption of beef in the diet. We found that a nonvegetarian diet exacts a higher cost on the environment relative to a vegetarian diet. From an environmental perspective, what a person chooses to eat makes a difference.