No, in "real life," this [probably] does not happen

While the paper establishes what it says... it is based on computer simulated social networks and does not track with actual human behavior/psychology.

Answer from full text PDF of the article being discussed, "Social consensus through the influence of committed minorities", Physical Review E Vol. 84 Issue 1, July 2011.

The paper simulates person-to-person interactions in a social "network" by creating a system of nodes governed by something called binary agreement model, summarized by the paper this way:

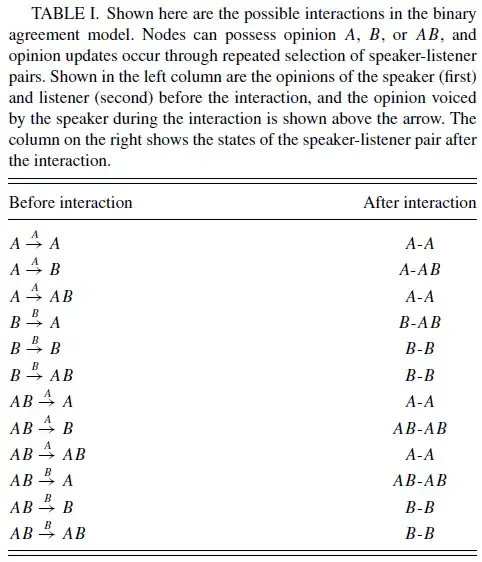

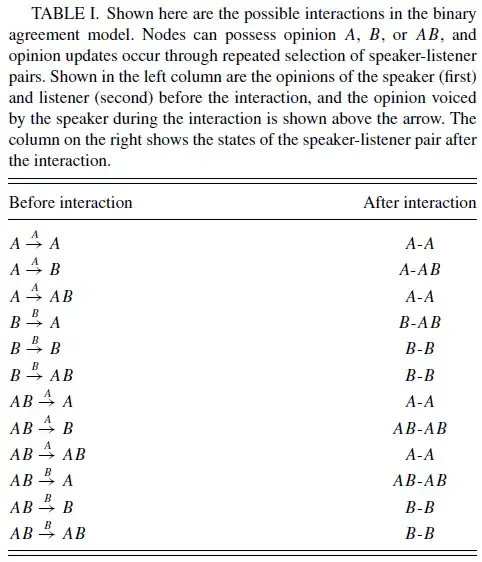

The evolution of the system in this model takes place through the usual NG dynamics, wherein at each simulation time step a randomly chosen speaker voices a random opinion from his list to a randomly chosen neighbor, designated the listener. If the listener has the spoken opinion in his list, both speaker and listener retain only that opinion, or else the listener adds the spoken opinion to his list (see Table I).

Table 1 from the paper, showing the potential variations between speaker and listener for two opinions, A and B, is shown here:

The study did the following to determine how "unshakable opinions" would influence things:

Here, we study the evolution of opinions in the binary agreement model starting from an initial state where all agents adopt a given opinion B, except for a finite fraction p of the total number of agents who are committed agents and have state A. Committed agents, introduced previously in, are defined as nodes that can influence other nodes to alter their state through the usual prescribed rules, but which themselves are immune to influence.

So, in essence, this means that if we have a network of nodes having a distribution of opinions A and B, playing by the rules of the binary agreement model, over time, the majoriby view will win out. But, this study introduced some nodes, say containing belief A, that could influence others, but not be influenced. Rewriting the above table for uninfluencable nodes gives this new variant:

S=speaker

O=opnion spoken

L=listener

| S | O | L | Normal Outcome | Outcome faroving A |

|----+---+----+----------------+--------------------|

| A | A | A | A-A | A-A |

| A | A | B | A-AB | A-AB |

| A | A | AB | A-A | A-A |

| B | B | A | B-AB | B-A* |

| B | B | B | B-B | B-B |

| B | B | AB | B-B | B-AB* |

| AB | A | A | A-A | A-A |

| AB | A | B | AB-AB | AB-AB |

| AB | A | AB | A-A | A-A |

| AB | B | A | AB-AB | AB-A* |

| AB | B | B | B-B | AB-B* |

| AB | B | AB | B-B | AB-AB* |

|----+---+----+----------------+--------------------|

I've starred those outcomes that are different. What we have with these uninfluenced nodes is that any AB speaker will not drop A when telling opinion B to a B listener; instead tehy will retain A. Any listener containing A alone will not add B to their list when told B by either a B or AB speaker.

In any case, this is surely enough to clarify that these are vastly simple rules carried out in a computer simulation. While I know that appealing to "common sense" and "logic" may be frowned upon, I'm dearly hoping I don't need a source to back up the statement that humans aren't this simple when it comes to adopting one opinion or another during person-to-person interaction.

It's hard to know whether the paper even attempts to say what ScienceBlogs says it does, though. For example, from the ScienceBlogs summary:

Scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have found that when just 10 percent of the population holds an unshakable belief, their belief will always be adopted by the majority of the society.

Note the word "always" -- this doesn't leave room for the type of belief, at least in my own read. Note this from the introduction of the actual paper, though:

The binary agreement model is well suited to understanding how opinions, perceptions, or

behaviors of individuals are altered through social interactions specifically in situations where the cost associated with changing one’s opinion is low, such as in the pre-release buzz for a movie, or where changes in state are not deliberate or calculated but unconscious. Furthermore, by its very definition, the binary agreement model may

be applicable to situations where agents, while trying to influence others, simultaneously have a desire to reach global consensus.

So, it appears that they were specifically looking at a simulation known to work acceptably for low-cost/low-investment "opinions/perceptions." I was far more interested in the implications for major beliefs such as religion, global warming, vaccines, etc. I'm leaning toward saying that this type of simulation has nothing to do with these types of strongly emotional, personal, family-history-influenced, local-culture, and [even sometimes!] evidence-based beliefs. It seems more suited toward simulations situations where individuals want to make a quick decision that is mostly irrelevant to the grand scheme, and move on.

The rest of the paper is primarily discussing the mathematical results of the simulations, illustrating what percentage of "unconvincable" nodes were required to win the overall group to a particular opinion.

Lastly, if this were true, one could wonder (thanks @vartec) why Macs have not taken over yet (Wiki on Apple market share, stating that they are at that 10% mark), or perhaps more obviously why the US hasn't entirely converted to some form of Christianity since about 78% of Americans are Christian. The most recent Pew Forum survey seems to indicate that non-belief, in the form of atheism/agnosticism, is actually on the rise. See page 24 for a table indicating that among those surveyed, a combined ~0.8% were atheists/agnostics in their youth, compared to ~4.0% when surveyed recently in adulthood.