The title asks a broader question, while the body seems to focus on something more specific. Since CJR's answer seems to have addressed the more specific question, I'll try to address the broader one.

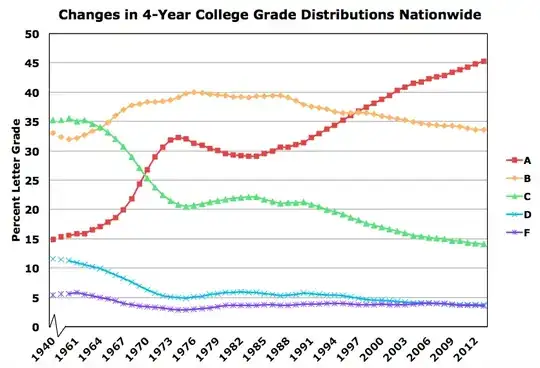

Yes, this is extremely well documented, and the trend has not been at all subtle. A good book on the topic is Grade Inflation: A Crisis in College Education, by Valen Johnson. Grade inflation has been especially pronounced at schools with highly selective admissions and in the humanities and liberal arts. It exists, but is less extreme, in STEM fields and at community colleges and other less selective institutions.

Popov and Bernhardt have collected a lot of data as a function of time. As an example, here are their numbers from Yale for average GPAs:

- 1960: 2.56

- 1980: 3.27

- 2000: 3.48

One could ask whether students are just doing better work these days, so that they deserve the better grades, but actually there is a lot of evidence that they are assigned less reading and writing than in the past, and that their critical thinking skills develop less now than they did in the past. This is discussed in Academically Adrift, by Arum and Roksa, who also demonstrate that the lower outcomes are not just because a broader demographic is going to college.

Johnson did some very clever studies to show that there really is a difference between STEM and non-STEM fields, and also that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between grades and student evaluations of teaching. For STEM/non-STEM, he looked at grades for both STEM majors and non-STEM majors in STEM and non-STEM classes, i.e., closer to or farther from their own specialization. For the cause-and-effect relationship, they devised a ruse in which students were allowed to give online teaching evaluations, then saw their grades, and then were asked to redo the teaching evaluations. They found that students revised their evaluations based on their grades.

A popular theory is that this trend really got going in the US during the Vietnam era, because professors didn't want students to drop out and get drafted. The beginning of the trend also coincided in time with the period when student evaluations of teaching became a thing, so that there was more pressure on instructors to give good grades. Part-time faculty are especially vulnerable to these pressures, and the trend toward teaching as many classes as possible using part-timers dates to roughly the same period. However, as far as I know these cause-and-effect relationships are not objectively documented in any scientific way. Anecdotally, though, the pressure from student evaluations is pretty obvious, though, for anyone who's been on a tenure committee or has been involved in hiring and retention decisions involving part-time faculty.