Was it cheaper to starve a slave to death and to replace him than it was to provide him with food? It depends on what you mean with "starve".

Starve has two meanings according to Merriam-Webster:

1a : to perish from lack of food - b : to suffer extreme hunger

Definition #1

If we were to take the first definition, the claim would come down to:

A slave was at some point in time cheaper than the food required to keep him alive.

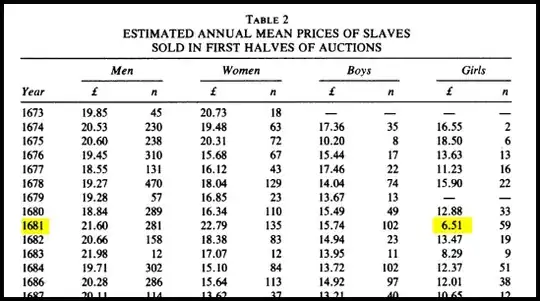

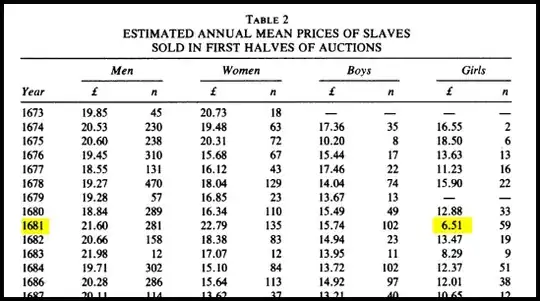

How expensive was a slave? Seeing as the context of the claim referred to the slave trade in Jamaica, we will use the slave trade in Barbados as reference. Galenson (1982) calculated that the cheapest point in time to buy a slave was in 1681, where £6,51 could get you a slave girl (see image).

Using this currency converter I found online, £6,51 in 1681 was worth almost $1.600 in today's money. Assuming this currency converter is half decent, I consider it to be highly improbable that there was a point in time in Barbados where a slave was cheaper than the food required to keep him alive.

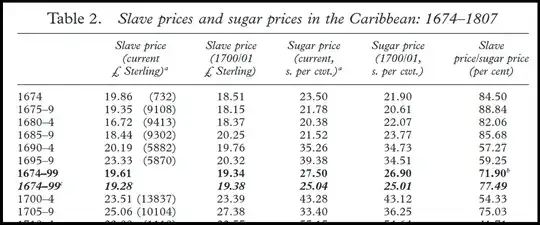

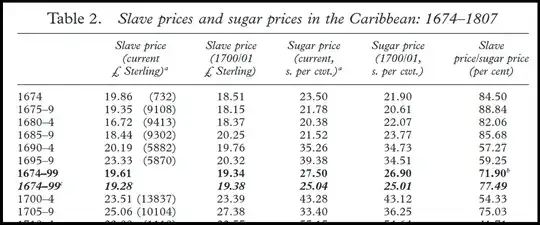

EDIT: I did a little more digging and found the following table by Eltis et al.

This table shows that at the lowest point a slave was worth about 420KG* of sugar. I assume sugar was a relative expensive product in those days, meaning that they were probably worth a lot more than 420kg of "normal" food.

*1710-1714 sugar prices were 54,64s/cwt = £2,73. Slave prices in 1710-1714 were £22,55, so 1 slave was worth 8,25cwt = 420KG of sugar.

What about the second definition by Merriam-Webster?

Definition #2

If we were to take the second definition, the claim would come down to:

It was cheaper to keep a slave malnourished and to replace him when he prematurely dies, than to keep the same slave well fed during the same period of time.

Handler and Corruccini (1983) wrote about the plantation live in Barbados (emphasize mine):

Dirks calculates caloric levels and protein intake. He concludes that plantation food allowances were clearly inadequate "to the total energy required by the average field laborer," and that protein rations were also "marginal at best and more likely inadequate to the extraordinary demands of life and labor on a West Indian estate." Moreover, the foods that the slaves provided for themselves did not augment plantation food allowances sufficiently to produce "an overall level of nutritional adequacy." Dirks's findings can be extended to Barbados, where the historical and physical anthropological evidence support a view of a malnourished slave population.16

Regarding the reason for the malnutrition, they write (emphasize mine):

Plantation allocations varied as a result of a variety of factors within the control of individual managements: for example, what they were willing to spend on food in their efforts to maximize profits and reduce costs and how much acreage they were prepared to plant in food crops. Factors beyond their control also affected food allocations as, for example, when a disruption in trade patterns caused an increase in imported food prices with a concomitant skimping on slave rations, and when droughts, storms, and hurricanes affected the supply of locally grown foods and severely reduced the slaves' diet, sometimes to the point of producing famine conditions.

I couldn't find a source that actually did the cost-benefit analysis of slave malnutrition, but Handler and Corruccini write there were plantation owners who at least acted like it was good economics.

Conclusion

Based on what I could find, I consider it highly unlikely (but your mileage may very) that there was a culmination of circumstances that led to slaves being cheaper than the food required to keep them alive. However, according to Handler and Corruccini (1983) slaves were routinely malnourished in order to "maximize profits and reduce costs". So the claim is true from at least one perspective. Seeing as the first definition is a very extreme interpretation (IMHO), and considering the

Principle of Charity, I am comfortable with saying that the claim is true.

Edit: some final notes. The answers to this question depend on how the claim is interpreted. During my research for this answer I found an anecdote, I can't find it anymore but I believe it was by Frederick Douglass, where a lame female slave was flogged and send away because she was useless to her master. The anecdote concluded that she likely starved to death. Does that mean that the claim is true? In this specific case her owner decided that she was worth absolutely nothing, does that verify the claim? Or is the claim about the widespread use of this practice during economic hard times? The ambiguity makes the question hard to answer, but I hope this answer brought some perspectives that are helpful.

References

Galenson, D. W. (1982). The atlantic slave trade and the Barbados market, 1673-1723. *Journal of Economic History*, 491-511.

Eltis, D., Lewis, F. D., & Richardson, D. (2005). Slave prices, the African slave trade, and productivity in the Caribbean, 1674–1807 1. The Economic History Review, 58(4), 673-700.

Handler, J. S., & Corruccini, R. S. (1983). Plantation slave life in Barbados: A physical anthropological analysis. The Journal of interdisciplinary history, 14(1), 65-90.

Further Reading

Aworawo, D. (2010). Bitterness on a Sugar Island: British colonialism and the socio-economic development of Jamaica (1655-1750). *Lagos Notes and Records, 16(1)*, 189-214.