Haven't yet located an actual school book from that time.

But this is in line with old territorial claims of China, thus not really tying this "tradition" to either Tibet or "Red China" (Nationalist Republic of China aka Taiwan did and does the same)or 1951:

Joseph Newman: "A New Look at Red China" Washington: U.S. News & World Report, 1971. (archive.org)

Joseph Newman: "A New Look at Red China" Washington: U.S. News & World Report, 1971. (archive.org)

(src)

(src)

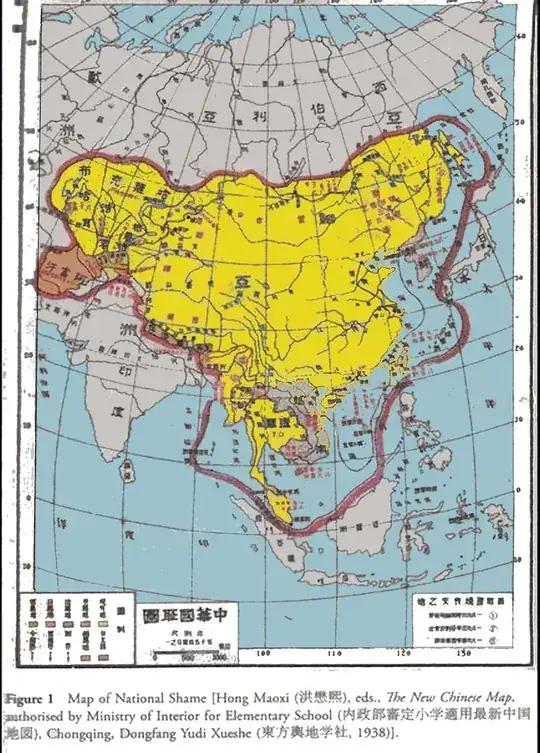

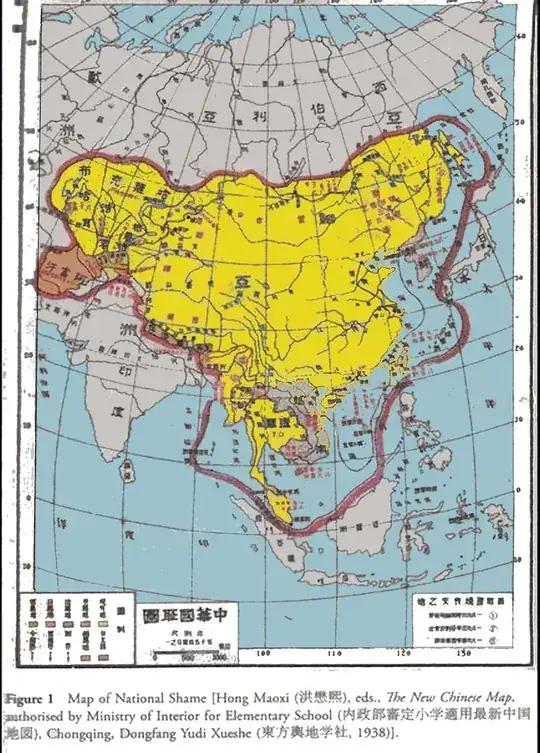

(Note the time and date for this map: this is was the provisional capital of the Republic of China RPC under the nationalist Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang)

More of this kind at Global Security.org: China National Humiliation Maps, and also explained in detail in the chapter "Where is China" in William A. Callahan: "China. The Pessoptimist Nation", Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York, 2010. (p 91–125):

As early as July 1915, a national curriculum for national humiliation education emerged to guide people’s understanding of identity and security; national humiliation history and geography textbooks soon followed. As Sun Xiangmei explains, “Through National Humiliation education at school, public debates, and guidance by patriotic organizations, it is not surprising that National Humiliation Day became an unforgettable memory for the vast majority of youth and students” in the Republican era. In this way, Chinese nationalism is one of the products of National Humiliation Day, not just in terms of ideas, but in terms of the institutional practices of nationwide social movements and national curricula.

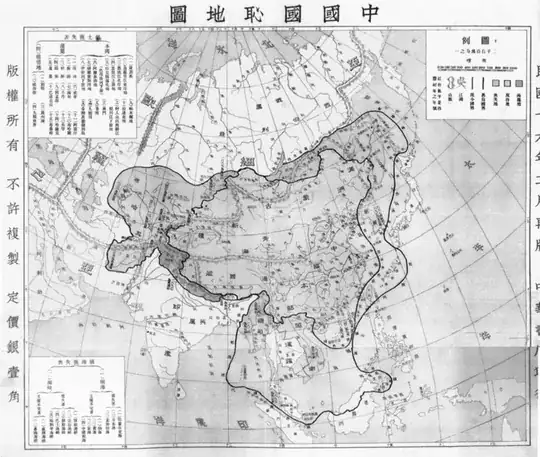

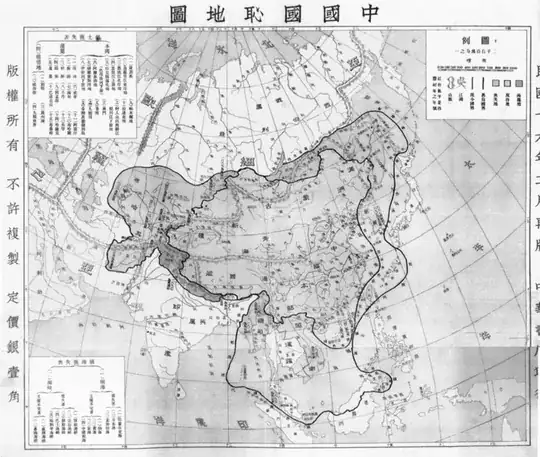

The 1927 map lists fifteen lost “homeland territories,” fifteen lost “vassals,” four “territorial concessions,” and another fourteen lost and disputed “maritime territories.”

Some of these “lost territories” now seem obviously “Chinese”: Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan were ceded in treaties to the British, Portuguese, and Japanese empires. But other lost territories are not so obviously Chinese possessions: the map claims most of the countries in what we now call Southeast Asia and Central Eurasia, as well as Korea and the Russian Far East in Northeast Asia, and the Himalayan states of South Asia. Moreover, all the national humiliation maps dot China’s geobody with notes (often in red ink) that mark treaty ports, massacres, and other wounds to the geobody from the Century of National Humiliation.30 The Geography of China’s National Humiliation (1930) textbook makes the political purpose of such illustrations and annotations clear; it states that since China has lost more than half its territory, it is necessary to “compile a geographical record of the rise and fall of our country in order to craft a government policy to save it.”

This set of national humiliation maps of lost territories thus seeks to combine the expansive cosmology of late imperial maps with the scientific geography of maps of China’s sovereign territory. Through the logic of outside/in and inside/out, China’s early-twentieth-century cartography asserted the proper shape of “the real China” as a combination of late imperial and modern notions of space.

Figure4.7 Map of China’s national humiliation (1927). Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Colour versions to be found in William A. Callahan: "The Cartography of National Humiliation and the Emergence of China’s Geobody", Public Culture 21:1, 2009. doi 10.1215/08992363-2008-024. (PDF)

Depending on how to read the claim – as in the question title: yes, China was mapped to be significantly larger, claiming territories in the central Asian republics –– but as quoted: strictly reading, no, this did not begin in/circa 1951, as this was established policy long before and still is.