Interestingly there's a survey: "Biologists' Consensus on 'When Life Begins'", 2018 of US biologists on this (the choice of profession/experts was motivated by a pre-survey of the US population at large):

Many Americans disagree on ‘When does a human’s life begin?’ because the question is subject to interpretive ambiguity arising from Hume’s is-ought problem. There are two distinct interpretations of the question: descriptive (i.e., ‘When is a fetus classified as a human?’) and normative (i.e., ‘When ought a fetus be worthy of ethical and legal consideration?’). To determine if one view is more prevalent today, 2,899 American adults were surveyed and asked to select the group most qualified to answer the question of when a human’s life begins. The majority selected biologists (81%), which suggested Americans primarily hold a descriptive view. Indeed, the majority justified their selection by describing biologists as objective scientists that can use their biological expertise to determine when a human's life begins.

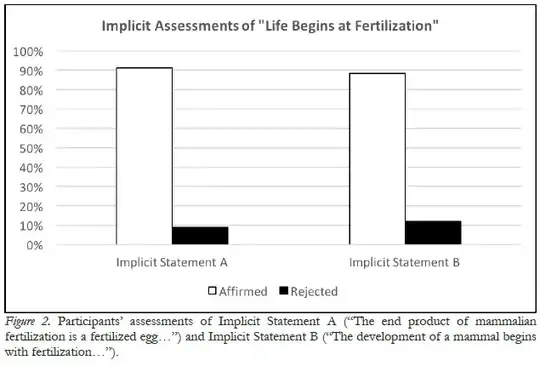

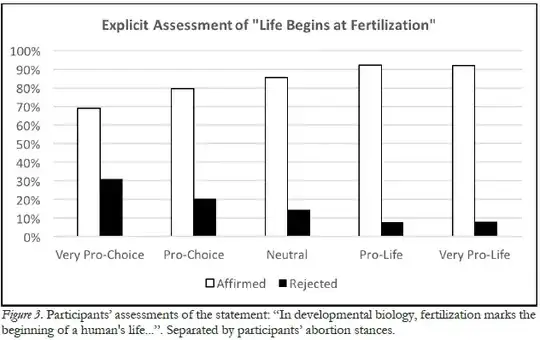

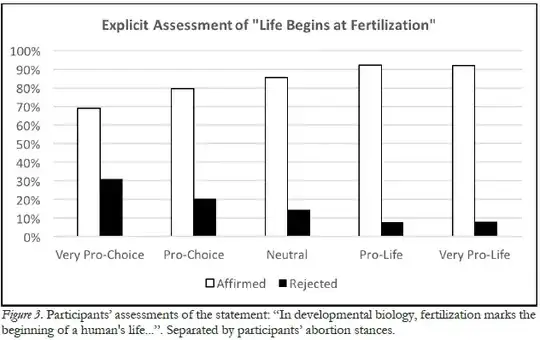

A sample of 5,502 biologists from 1,058 academic institutions assessed statements representing the biological view ‘a human’s life begins at fertilization’. This view was used because previous polls and surveys suggest many Americans and medical experts hold this view. Each of the three statements representing that view was affirmed by a consensus of biologists (75-91%). The participants were separated into 60 groups and each statement was affirmed by a consensus of each group, including biologists that identified as very pro-choice (69-90%), very pro-life (92-97%), very liberal (70-91%), very conservative (94-96%), strong Democrats (74-91%), and strong Republicans (89-94%). Overall, 95% of all biologists affirmed the biological view that a human's life begins at fertilization (5212 out of 5502).

Historically, the descriptive view on when life begins has dictated the normative view that drives America's abortion laws: (1) abortion was illegal at ‘quickening’ under 18th century common law, (2) abortion was illegal at ‘conception’ in state laws from the late 1800’s to the mid-1900’s, and (3) abortion is currently legal before ‘viability’ due to 20th century U.S. Supreme Court cases Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. While this article’s findings suggest a fetus is biologically classified as a human at fertilization, this descriptive view does not entail the normative view that fetuses deserve legal consideration throughout pregnancy.

But do note (as the 3rd para [I added the breaks for readability] says) that that doesn't imply anything about viability/personhood. The fact that these are distinct questions is emphasized in other (scientific) sources, e.g. Kurjak et al.:

In this paper we show that the question, "When does human life begin?", is not one question, but three. The first question is, "When does human biological life begin?", and is a scientific question. A brief review of embryology is provided to answer this question. The second question is, "When do obligations to protect human life begin?", and is a question of general theological and philosophical ethics. A brief review of major world religions and philosophy is provided to answer this question but has no settled answer and therefore involves irresolvable controversy. The third question is, "How should physicians respond to disagreement about when obligations to protect human life begin?" and is a question for professional medical ethics.

The science in this latter paper is nothing unconventional, i.e. it's consistent with the majority view from the other one.

Some (interesting, I hope) details from the survey (first paper). They asked 4 question of biologists:

Q1 - Implicit Statement A: “The end product of mammalian fertilization is a fertilized egg (‘zygote’), a new

mammalian organism in the first stage of its species’ life cycle with its species’

genome.”

Q2 - Implicit Statement B: “The development of a mammal begins with fertilization, a process by which the

spermatozoon from the male and the oocyte from the female unite to give rise to a

new organism, the zygote.”

Q3 - Explicit Statement “In developmental biology, fertilization marks the beginning of a human's life since

that process produces an organism with a human genome that has begun to develop

in the first stage of the human life cycle.”

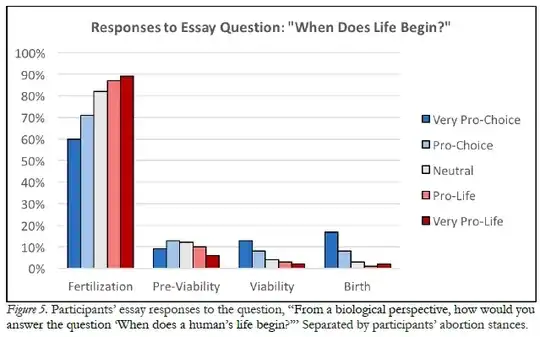

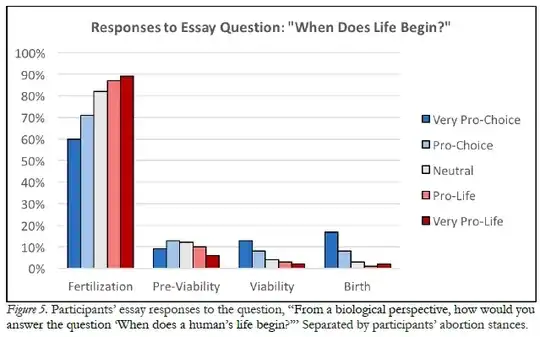

Q4 - Open-Ended Essay Question: “From a biological perspective, how would you answer the question ‘When does a

human's life begin?’”

And some charts for the responses (for the first two questions there was no [graphical] breakdown of political orientation; there is some in a table, but it's two pages long):

For the last question, there was manual coding of the free-form responses into those categories.

The "95% consensus" may be a little exaggerated because it was derived by evaluating whether each subject affirmed at least one of Q1-Q3 (i.e. logical ORing).

LangLangC asks some interesting (terminology) questions. One way to solve these is as in the 2nd paper I mentioned (Kurjak et al.):

A human being originates from two living cells: the

oocyte and the spermatozoon, transmitting the torch of

life to the next generation. [...] After syngamy, the zygote undergoes mitotic cell division

as it moves down the fallopian tube toward the

uterus. A series of mitotic divisions then leads to the

development of the preembryo. [...]

The pre-embryo is the structure that exists from the

end of the process of fertilization until the appearance of

a single primitive streak. Until the completion of implantation

the pre-embryo is capable of dividing into multiple

entities, but does not contain enough genetic information

to develop into an embryo: it lacks genetic material from

maternal mitochondria and of maternal and parental

genetic messages in the form of messenger RNA or

proteins.

A key stage in embryonic development is the emergence

of an individual human being. ‘‘Individual’’ means

that an entity (1) can be distinguished from other entities

and (2) is indivisible, i.e., it cannot be divided or split into

two members of the same species. An entity meeting the

first criterion, but not the second, is a distinct but not

individual entity. The pre-embryo, because it can divide

into monozygotic twins is a distinct but not individual

entity. The embryo, by contrast, no longer divides into

monozygotic twins and so it meets both criteria for being

an individual.

Distinct human life begins when there is a distinct entity,

the pre-embryo, resulting from the process of conception.

There is no ‘‘moment’’ of conception, a phrase that

has no biological application. Individual human life

begins later, with the emergence of the embryo. There is

no ‘‘moment’’ at which this occurs either. The beginnings

of human life involve complex biological processes that

occur over time.

The latter terminology "distinct human life", "individual human life" is probably not so well-established... But in this sense, an (unfertilized) egg or sperm is not "distinct human life" from its host/producer.

Here is a contrary opinion in more detail, from a physician:

What is scientifically incorrect about saying that human life begins at fertilization? First, it is a categorical designation in conflict with the scientific observation that life is a continuum. The egg cell is alive, and it has the potential to become a zygote (a single-celled embryo) if it is appropriately fertilized and activated by a live sperm. If fertilization is successful and the genetic complement of the sperm is added to that of the egg, the resulting zygote is also alive. The zygote has the same size as the egg; other than for its new genotype, the cell (comprising the cytoplasm and the rest) is nearly identical to the egg cell. From a biological perspective, no new life has been created.

Second, “human life” implies individuality, which is also not consistent with scientific observations. In the clinical practice of IVF, we often speak of preimplantation embryos as individual entities, with distinct qualities like a specific genotype (mosaicism notwithstanding), and morphologic and developmental characteristics. But at the same time we realize that each of the totipotent cells that comprise these embryos is, at least theoretically, capable of producing a complete new individual. Indeed, multiple individuals can arise from the implantation of a single embryo, as in the case of identical twins. Therefore, we know that the preimplantation embryo is not actually an individual. The preimplantation embryo is essentially an aggregate of stem cells, which has the potential to produce a pregnancy, including placental and fetal tissues, assuming that it successfully implants in a receptive endometrium. It is only after implantation that the early embryo can further differentiate into the organized cell groups that enable the developing conceptus to progress further in embryonic and eventually fetal development.

The facts are basically the same as in the previous quote. It's a matter of interpretation/terminology.

Somewhat diverging on facts are some (mostly recent) studies which delve into syngamy. They found that in some non-human mammals and in some in-vitro human fertilizations it may take a few cell division for syngamy to (fully) complete; in the meantime the genetic materials may still be somewhat or mostly separated. These finding at the very least enhance the view that talking of a "moment" when life begins is a tenuous. From a 2018 journal editorial serving as a mini-review:

Syngamy has become an acceptable sentinel for the beginning of life. Nearly a century ago, a generation of cell and developmental biologists laid down the groundwork for the biology of fertilization in EB Wilson’s treatise of 1925. Compiled, congealed, and constitutional in nature, tales of syngamy based on the tools of cytology recognized the importance of that special moment in the life history of all sexually reproducing metazoans. That nuptial encounter between the genomes of mom and dad, with the subsequent and equivalent segregation of maternal and paternal chromosomes on a mitotic spindle, has become a building block for our understanding of how embryo development is launched on the pathway to implantation and beyond. That the sperm brings more than a genome to this BYOB (bring your own bottle) affair has long been accepted in the case of humans, emphasizing the role of the paternally inherited centrosome in construction of that first bipolar mitotic spindle.

Fast forward 75 years to the prescient work of Mayer and colleagues, where in an elegant series of experiments on mouse embryos, the stage of development when mom and dad consummate their genome merger is called into question (a probable reason why this work has been virtually buried in the literature). These papers suggested that maternal and paternal chromosomes retained a spatially exclusive location within blastomere nuclei through the first three cell cycles, after which both genomes became spatially integrated into one.

Since these studies were published, the development and application of live cell imaging techniques has blossomed in many biomedical research disciplines. And among those pushing the limits of conventional and novel microscopic techniques in human ARTs (assisted reproduction technologies), and willing to overcome some of the methodical obstacles associated with monitoring living human embryos, is the laboratory of Professor Mio and his collaborators [...]. Among their accomplishments has been the implementation of high resolution microscopy capable of revealing dynamics of cell motility in human embryos and the identification of a novel mechanism operative during the block to polyspermy. Supplementing this technology with spinning disk imaging of fluorescent reporters of chromosomes and spindle components, and differential labeling of maternal and paternal genomes, the present study aimed at evaluating the fate of single pronuclear stage embryos, and in the process uncovered much more. Could it be that, as in the mouse, parental genomes exhibit some degree of autonomy relative to each other?

Their findings are to be interpreted with caution given the source of embryos, the manipulations required to both express and track biomarkers, and the limited number of samples being investigated. However, if repeated and confirmed, these results extend an ongoing conversation suggesting that zygotes of several mammals, including the human, engage in processes that delimit the final integration of maternal and paternal genomes to some as yet undetermined stage within or beyond the initial cell cycles.

[...] in closing that we draw attention to the most recent work coming from the EMBO laboratories of Jan Ellenberg in Heidelberg for both the technological bravado and surprising findings in the mouse zygote regarding separation of maternal and paternal genomes. In essence, what they have now accomplished using light sheet microscopy is to reveal the gender-specific generation of spindles for mom and dad that ultimately converge into one before effecting anaphase on the way to the two-cell stage. Unlike the work of Mayer et al. cited above, their results detected genome integration in two-cell embryos.

Collectively, these observations are causing much head-scratching as we await the results of similar studies on the human conceptus. We have reached a point where foundational concepts such as syngamy may have to be re-visited, not only to deepen our understanding of early human development but also provide a science-based infrastructure upon which societal and ethical guidelines will be formulated based on solid observation and not historical bias.

The are probably quite a few other positions, but it's harder to tell how widespread they are; e.g. there's a 1984 paper (with ~50 citations in Google Scholar) in a medical ethics journal arguing that brain activity marks the beginning of human life:

In an attempt to provide some clarification in the abortion issue it has recently been proposed that since 'brain death' is used to define the end of life, 'brain life' would be a logical demarcation for life's beginning.

Actually the same view is taken in a 1985 paper which has more citations (~100). There's also some published criticism of this idea; it seems to center on the view that brain death is itself not well defined, i.e. there are multiple conceptions of that process/state too.

The whole brain definition of death refers to the

loss of major brain regions, including the brain

stem. Is there a parallel at the beginning of life?

Employing the appearance of brain stem functioning as one's criterion, brain birth would be placed

at around 6-8 weeks gestation. I shall refer to this

as brain birth I, which is a vitalist interpretation,

with its emphasis on biological integration and its

stress on mere human biological life. In contrast, a

second definition may be determined by the

beginning of consciousness at 24-36 weeks gestation. This is brain birth II, which parallels the personalist overtones of the higher brain definition of

death, with a sufficiently well-developed neural

organization to serve as the substratum from

which self-consciousness and personal life subsequently emerge.

And I suppose I should mention here that viability--currently the most medically relevant notion for abortion (but not for other contexts like "the day after" pill, IVF, etc.)--is not a purely biological notion, but rather it intersects with (medical) technology; quoting the obvious from Kurjak et al.:

Viability must be understood in

terms of both biological and technological factors,

because it is only by virtue of both factors that a viable

fetus can exist ex utero [...]

And I'm not quoting more because that (2007) paper is somewhat obsolete in this respect; Wikipedia has a decent coverage of developments in the past decade in artificial uterus technology. More detailed discussions of viability are also concerned with the quality of life aspects, not mere survival, e.g.

in the study by Rysavy et al., the rate of survival without moderate or severe morbidity in those 22-week-old infants was 9%.

Consequently, there's criticism (in that paper) of fixed gestation-age cutoffs in abortion legislation.