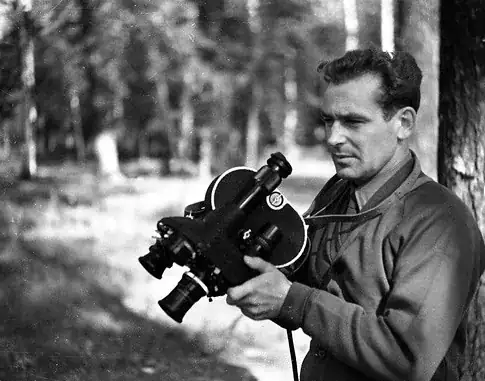

I could not (yet) find details of the camera affixed inside Gagarin's capsule, but only a few months later, Gherman Titov, carried a mobile 35mm camera (depicted below) in the Vostok 2 flight:

Titov used a 35-mm Konvas movie camera to shoot scenes out the window of his Vostok capsule. Some of the photos appear in an exhibit that opened at Moscow’s FotoSoyuz gallery this week, titled “50 Years of Space Photos.”

The camera is reasonably small, as you can see (even though here it's pictured on earth; the captions goes "Titov practices with a Konvas movie camera (Photo: FotoSoyuz)")

All Vostok space flights used the same reentry capsule, Vostok SA (Spuskaemiy apparat).

A bit of Titov's footage can be seen on youtube... and this includes footage of the Earth clearly take with some camera that's not unlikely to have been handheld, and also shows Titov holding the mobile camera in his suit, the latter images presumably taken by a fixed camera on board:

Also, below is an archival photo with people standing right next to a Vostok capsule (this is the Vostok-6 flight). (There's also archival footage of the same scene.) The argument that a camera would not fit inside (even alongside a human) is clearly silly without any calculation.

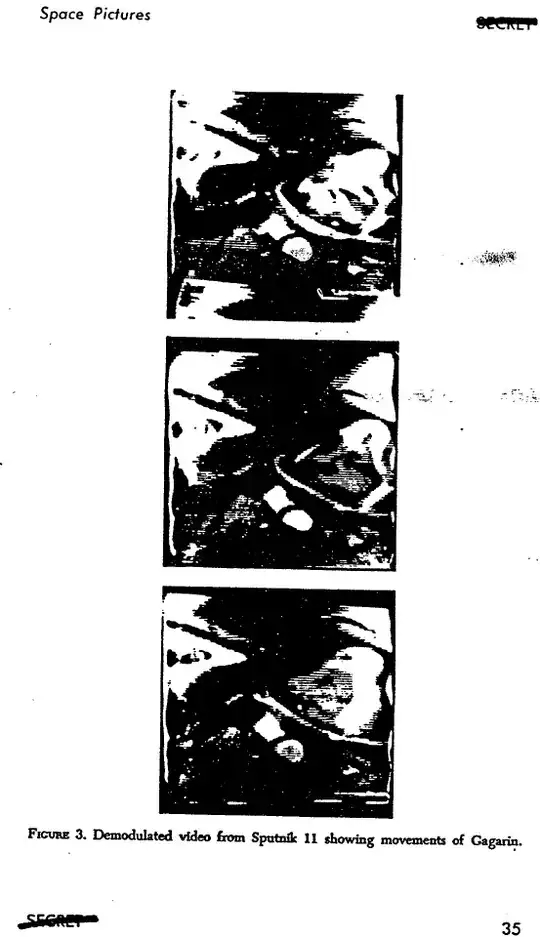

And perhaps an even more convincing evidence is that US agencies (CIA and later NSA) decoded the Soviet space TV transmissions nearly in real-time. From a declassified 1964 US document, "Snooping On Space Pictures":

Sputniks 5 and 6, launched respectively on 19 August and 1 December

1960, both transmitted signals on 83 megacycles which were

initially reported by field Elint operators and later confirmed through

detailed analysis to be video transmissions. Soviet announcements

that the dog passengers on these satellites were being watched while

in orbit by means of a "radio-television" system spurred on analytical

efforts to demodulate this new type of signal. And before long CIA

technical analysts did succeed in producing pictures from Sputnik 6's

recorded signals. (See Figure 2.) These substantiated the Soviet

claim of having developed a special television transmission system

which could provide instantaneous reporting on the behavior of animal

or human passengers aboard a Soviet spacecraft.

More important to intelligence in early 1961, however, was the establishment

of a capability to determine as soon after launch as possible

whether the Soviets had successfully orbited the first man in space, a feat they were expected to attempt at any moment. The National Security Agency undertook to design and produce special field collection equipment that would present oscilloscope pictures while the transmission was being received. Several such sets were produced on a priority basis, and the first two were sent to Elint sites in Alaska and Hawaii. Demodulation of video transmissions from Sputnik 9 (9 March 1961) and Sputnik 10 (25 March 1961) substantiated the Soviet announcements that each of these single-orbit flights carried a dog passenger.

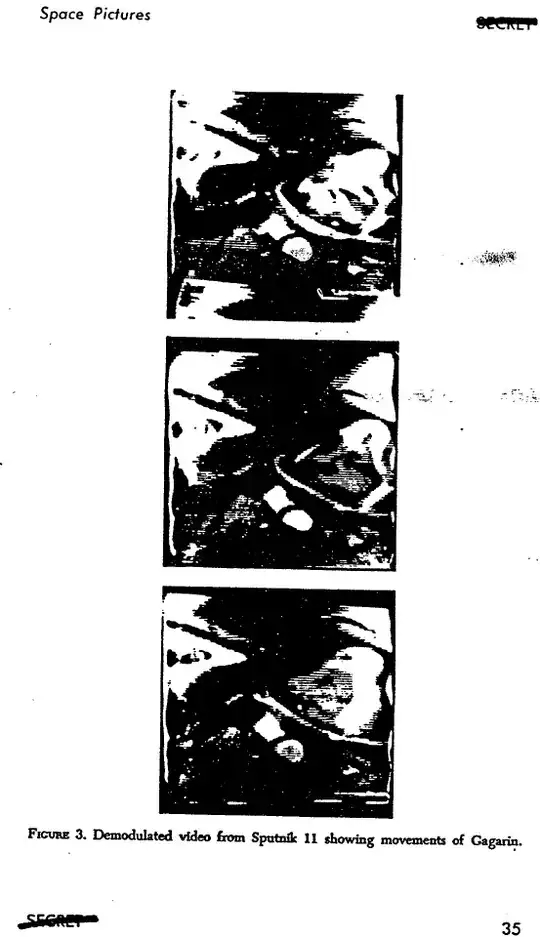

Then on 12 April 1961 Sputnik 11 was launched, and a 83-megacycle

transmissions were detected twenty minutes later as the spacecraft

passed over Alaska. Only 58 minutes after launch NSA reported that

reliable real-time readout of the signals clearly showed a man and

showed him moving. Thus before Gagarin had completed his historic

108-minute flight, intelligence components had technical confirmation

that a Soviet cosmonaut was in orbit and that he was alive

(See Figure 3).

Note that these "Sputnik" designations were due in no small part to the fact that the "Vostok" name was kept secret by the Soviets at the time.