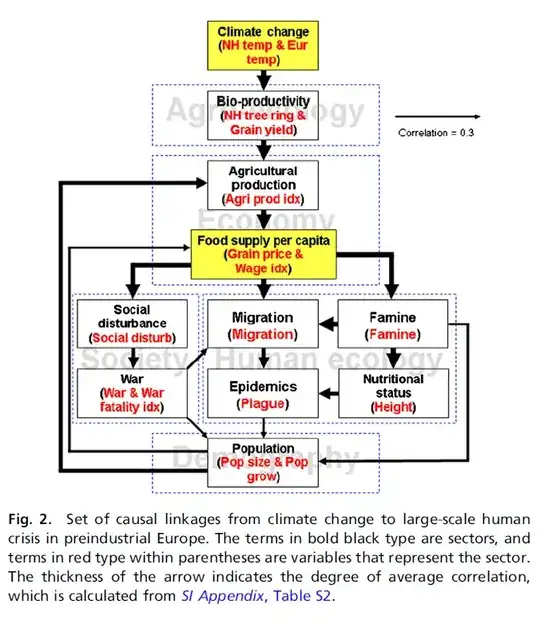

Since you were (apparently) thinking about line of research of David Zhang and his colleagues: yes they did find that cold weather historically promoted more wars and ultimately population decline, but they also found (2011) this was mediated by falling agricultural production:

Although agricultural production decreased or stagnated in

a cold climate, population size still grew. Hence, two variables of

[food supply per capita] FSPC—grain price and real wages of labor—changed considerably,

and economic crisis followed. Grain price is determined by

both demand and supply and is an important indicator of the

boom-and-bust cycle in an agrarian economy.

food supply per capita = FSPC

In other words, the same ultimate consequence on population could also happen if the weather get warm enough to have the same effect on agriculture, although historically that was not observed a lot in the data they looked at, except:

However, [in -- sic] the NH [Northern Hemisphere] warming also caused widespread famine between the 11th and 12th centuries (the Medieval Warm Period), because high temperature caused drought in North Africa and Western Asia [...]. However, the warmth was not severe enough to engender global crises.

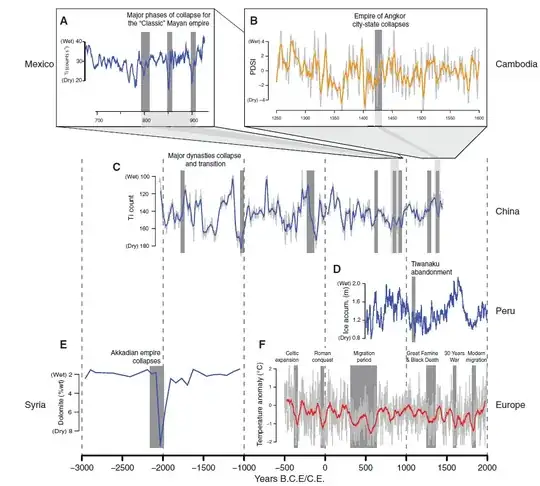

There are more historical examples (in both directions, but mainly droughts are outlined in the following figure) in a 2013 Science meta-analysis and review by Hsiang et al., which mostly covered papers on events in the modern era; there were not enough papers on the pre-industrial era for a meta-analysis of those, but I take it you're less interested in the modern era anyway:

The caption goes:

Fig. 3. Examples of paleoclimate reconstructions that find associations

between climatic changes and human conflict. Lines are climate reconstructions

(red, temperature; blue, precipitation; orange, drought; smoothed

moving averages when light gray lines are shown), and dark gray bars indicate

periods of substantial social instability, violent conflict, or the breakdown of

political institutions. (A) Alluvial sediments from the Cariaco Basin indicate substantial

multiyear droughts coinciding with the collapse of the Maya civilization. (B) Reconstruction of a drought index from tree rings in Vietnam, the

Palmer drought severity index (PDSI), shows sustained megadroughts prior to the

collapse of the Angkor kingdom. (C) Sediments from Lake Huguang Maar in

China indicate abrupt and sustained periods of reduced summertime

precipitation that coincided with most major dynastic transitions. The

collapse of the Tang Dynasty (907) coincided with the terminal collapse of the

Maya (A), both of which occurred when the Pacific Ocean altered rainfall patterns

in both hemispheres. Similarly, the collapse of the Yuan Dynasty (1368)

coincided with collapse of Angkor (B), which shares the same regional climate.

(D) Tiwanaku cultivation of the Lake Titicaca region ended abruptly after a drying

of the region, as measured by ice accumulation in the Quelccaya Ice Cap, Peru. (E) Continental dust blown from Mesopotamia into the Gulf of Oman

indicates terrestrial drying that is coincident with the collapse of the Akkadian

empire. (F) European tree rings indicate that anomalously cold periods were

associated with major periods of instability on the European continent.

Also note that there has been an opposing view to Hsiang et al. by Buhaug et al. (2014) although as far as I can tell that's about Hsiang's meta-analysis of papers on the industrial era. (For more on the Hsiang-Buhaug disagreement see Science Oct. 28, 2014.) I don't see (in Buhaug) an overt criticism of Hsiang's [pre-industrial] historical examples.

McMichael (2012) argued that temperature-wise the historical record is mostly biased by cold-temperature spikes, so that inferring the impact of climate changes from the direction (rather than the absolute magnitude) of temperature changes is mistaken:

• the nexus of drought, famine, and starvation has been the major serious adverse climatic impact on health over the past 12,000 y.

• Cold periods, more frequent and often occurring more abruptly than warm periods, have caused more apparent stress to health, survival, and social stability than has warming.

• Historical experience shows that temperature changes of 1 to 2 °C (whether up or, more frequently, down) can impair food yields and influence infectious disease risks. Hence, the health risks in a future world forecast to undergo human-induced warming of both unprecedented rapidity and magnitude (perhaps well above 2 °C) are likely to be great.

Analyzing some of the typical historical examples (in a somewhat obscure venue, I have to say), Diaz and Trouet (2014) conclude that

Drought appears to be the most common high-impact

stressor in the historical and prehistorical records. [... However] We emphasize that climatic changes alone are unlikely to be the sole determinant cause of a given

society’s response – whether abandonment of settlements or bellicose action against its own members

or neighbors. Often, the natural hazard is simply a catalyst for actions whose groundwork had been set

in motion for some time prior.

And as far as the anticipated global warming is concerned, that's bad news as well, i.e. an increase in drought is predicted for most areas of the globe that presently have high population density.