Summary:

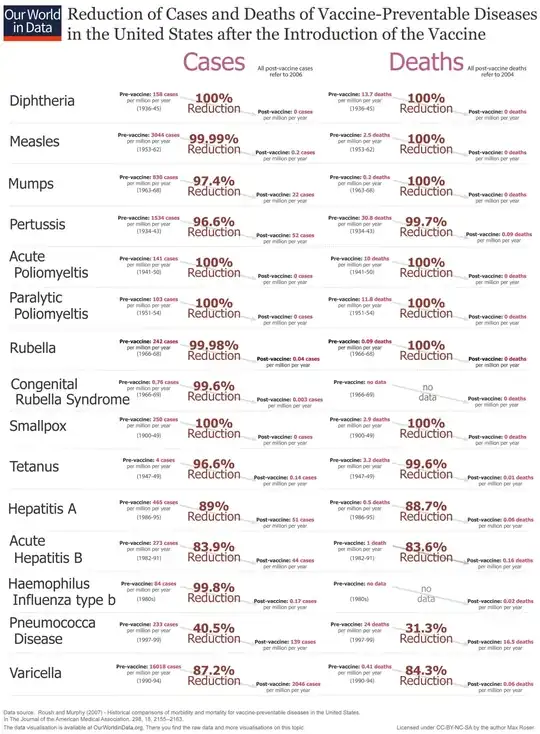

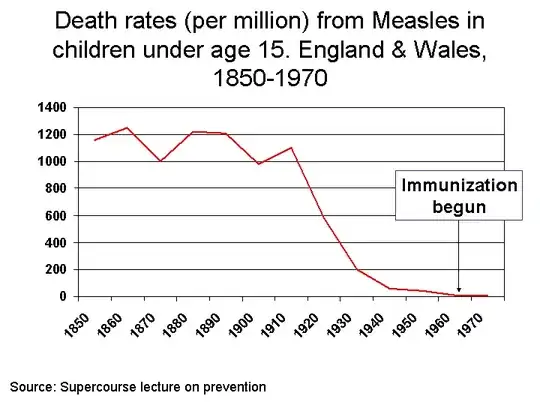

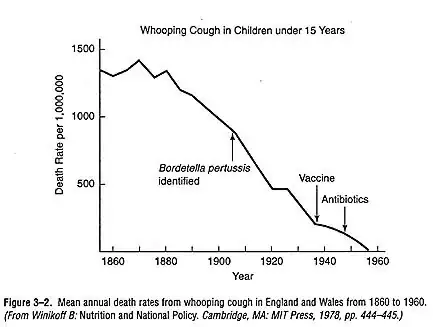

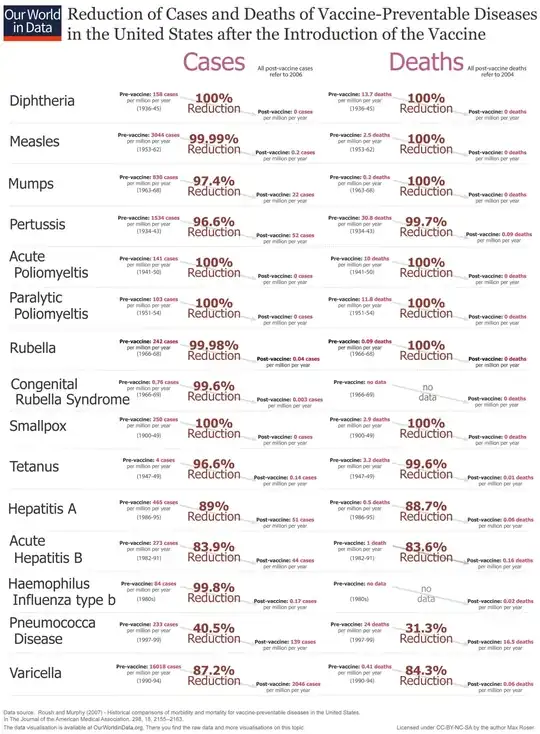

The main point of these claims is that the death rate for some diseases was declining before vaccines. While that is true, it misses the fact that even though the death rate was declining, plenty of people (mostly children) were still getting and suffering from these diseases. Vaccines dramatically decreased both the number of total cases, the severity of cases, and also the number of total deaths.

(Another thing worth mentioning, although not directly related to the claim, is that preventing a disease with vaccines means that antibiotics won't be used, and thus antibiotic resistance can't develop.)

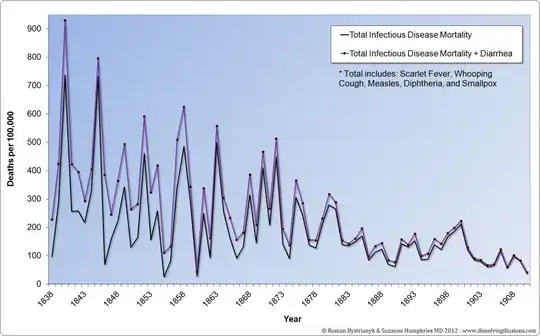

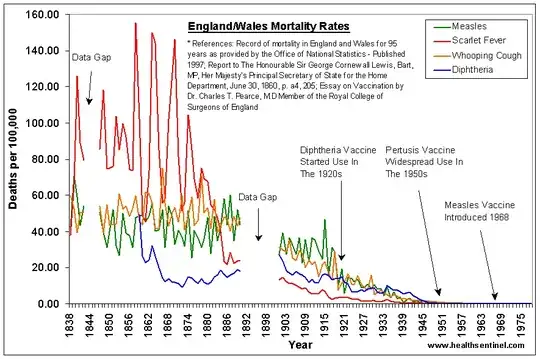

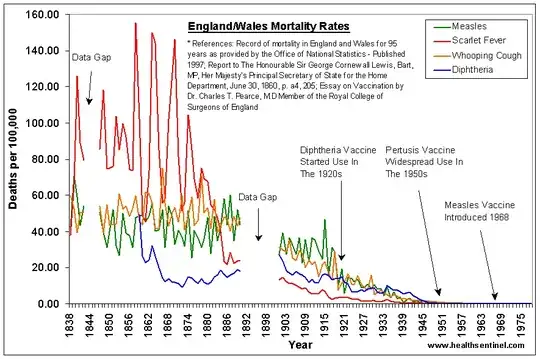

There are several problems with your graph: no sources, lumps four diseases in one line (including Scarlet Fever), and only has mortality (except for when they inexplicably include diarrhea...WTF?). So I'm going to address a similar graph, from another antivax site:

Archive Link

- I think that Scarlet Fever (also called Scarlatina) was included in the graph because it was grouped with diphtheria until 1861. (Or maybe they're trying to trick you.) There is currently no vaccine for Scarlet Fever, so it's pretty irrelevant here.

- The problem with only looking at the deaths is that for many of these diseases the treatment improved and fewer people died, but they were still getting infected in the first place.

- While there are...inconvenient...breaks in the graph, the data in the graph seems to be accurate. You can check the sources listed in the image if you want:

Death rate: 19th century

I found a paper that lists some 19th century disease statistics. The data is not as granular as in the graph, nor does it all go back as far as 1838 (and some of the stats cover the gap seen in the graph), but the data that is there matches up with the 19th century part of the graph well. The full paper also lists stats for Scarlet Fever and Smallpox.

Measles mortality rate per 100 000 living: 1838-1910

|

|

| 1838-42 |

53.9 |

| 1847-52 |

40.3 |

| 1856-60 |

42.5 |

| 1866-70 |

42.8 |

| 1876-80 |

38.5 |

| 1886-90 |

46.8 |

| 1896-1900 |

42.1 |

| 1901-5 |

32.7 |

| 1906-10 |

29.1 |

Death rate per million from Diphtheria: 1855-1893

[Divide by 10 to get rate per 100,000 as in the image.]

|

|

| 1855 |

20 |

| 1860 |

261 |

| 1865 |

126 |

| 1870 |

120 |

| 1875 |

142 |

| 1880 |

109 |

| 1835 |

163 |

| 1890 |

179 |

| 1893 |

302 |

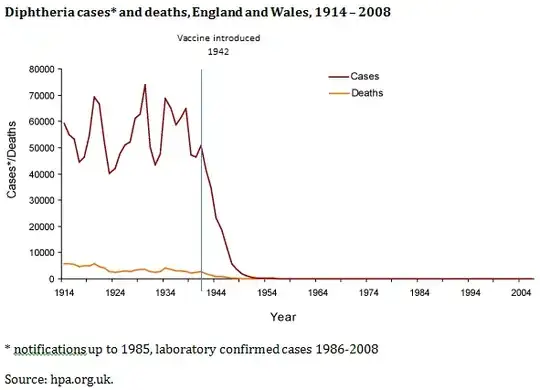

It was classified with scarlet fever until 1861; and because of the uncertainty of diagnosis, any conclusions about it must be speculative.

An antitoxin was discovered in 1894, but, as with all early antitoxins,

it had to be administered within the first four days of infection, which

is when symptoms are the least evident. However, the mortality did

decline from 9 446 deaths in 1894 to 7 661 in 1898. This fall probably relates to the wealthier classes, since the antitoxin was expensive, and not distributed free. It was 1913 before there was an effective diphtheria prophylactic and 1923, before the first safe vaccine was produced.

Whooping cough death rate per 1 000

[Multiply by 100 to get rate per 100,000 as in the image.]

|

|

| 1881-5 |

0.46 |

| 1886-90 |

0.44 |

| 1891-5 |

0.40 |

| 1896-1900 |

0.36 |

Anderson, Imogen (1993) The decline of mortality in the nineteenth century: with special reference to three English towns, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online:

http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5687/

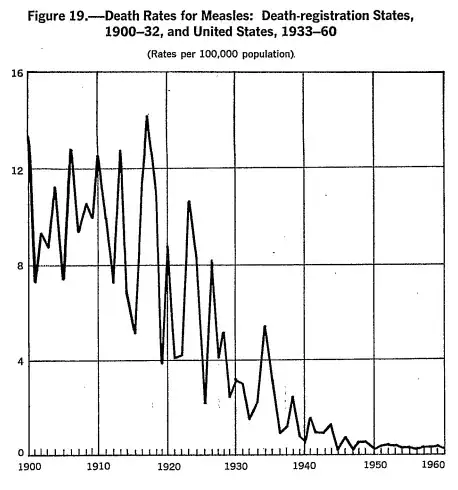

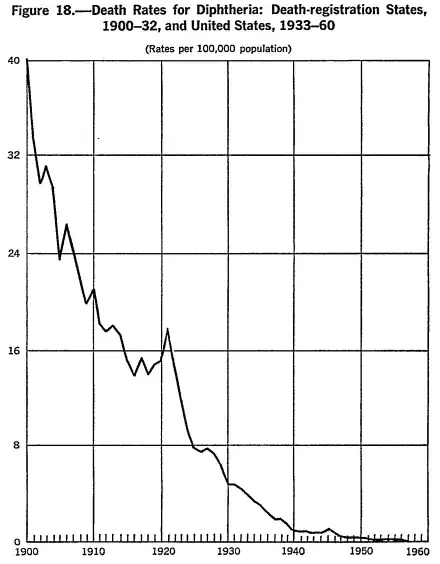

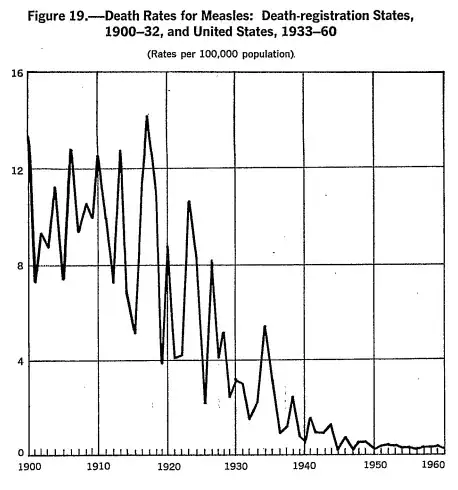

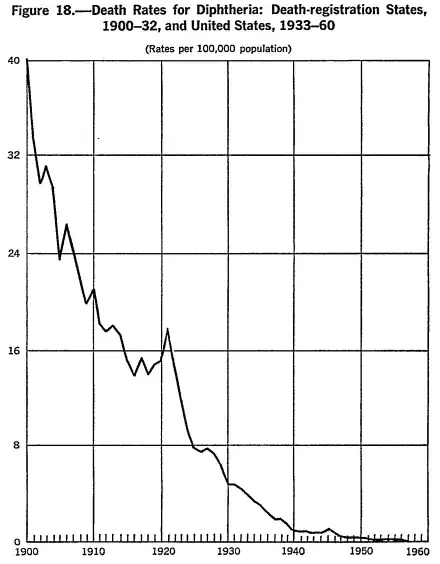

Death rate: 20th Century

I already linked to data for the UK/Wales, so I'll cover some US data. The CDC has Vital Statistics of the United States which go as far back as 1900. The PDF Vital Statistics Rates in the United States, 1900-1940 lists how many people per year died from various causes (but I'm only listing some years for three diseases):

Exclusive of stillbirths. By place of occurrence. Rates are the number of deaths per 100,000. Population estimated as of July 1 for 1900-1939 and enumerated as of Apr. 1 1940

|

1900 |

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

| Measles |

13.3 |

12.4 |

18.8 |

3.2 |

0.5 |

| Whooping Cough |

12.2 |

11.6 |

12.5 |

4.8 |

2.2 |

| Diphtheria[*] |

40.3 |

21.1 |

15.3 |

4.9 |

1.1 |

[* includes Croup for years 1900-1920]

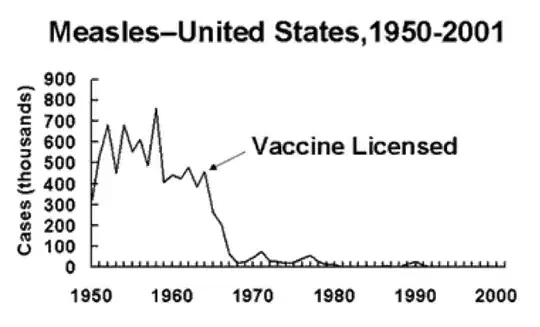

And some graphs (from the CDC):

[No graph for whooping cough]

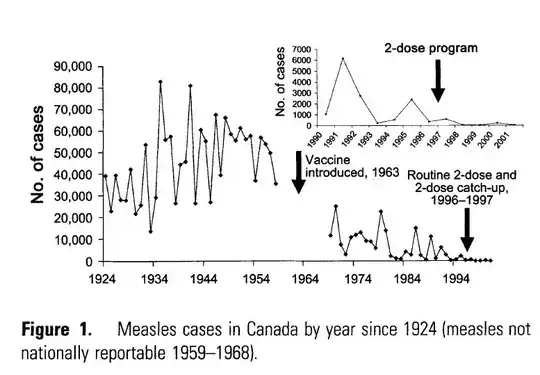

Death rate vs. All cases

Vaccines don't treat diseases; they prevent them. As a result, it's important to look at rates of incidence. If you look at the data, you'll notice that the rate of incidence is pretty high and then gets lowered after the vaccine is introduced. See this good article:

Here is a chart with lots of diseases:

Image Source: Our World in Data

These data are taken from Roush and Murphy (2007) – Historical comparisons of morbidity and mortality for vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. In the Journal of the American Medical Association, 298, 18, 2155–2163.

The same data can be viewed in a table here.

More