Andreoni, Nikiforakis and Stoop devised an improved version of the Scandinavian money-envelope experiment, which they ran in a Dutch city, and it didn't find the opposite effect, but failed to find a difference after adjusting for some confounders:

Our raw data indicate the rich behave more pro-socially. Controlling for pressures associated with poverty and the marginal utility of money, however, we find no difference in social preferences. The primary distinction between rich and poor is simply that the rich have more money

Also, whom the poor were (thinking they were) stealing from matters, in my opinion. In the Stoop experiment, the money was addressed to a middle-class Dutch neighborhood. So the poor (selected from social housing in the same city) were less likely to be "compassionate", money-wise about those likely richer than them. Would the result be the same if the money were addressed to a cancer-fighting charity? Or to a poverty-fighting charity? Or to some kid in Africa? It is actually known (granted from some laboratory studies) that

participants behave less prosocially (i.e., are less socially mindful) toward higher class targets relative to lower and/or middle class targets.

The Dutch study actually tried to control for this, unconvincingly in my opinion, by using the same middle-class address but rewriting the message so that it said that both the sender and receiver were cash-strapped (no details as to why were included in the message). And they found no difference in outcomes following this change in protocol.

The Dutch study found that the poor were less likely to return the money the closer they were to their pay check (which correlates negatively with how much money they had available). In fact this was their main finding:

While the difference in other arenas (such as tax evasion or charitable giving) may hinge on the fact that the rich have more money, in our study, the key fact seems to be that the poor have so little money. Our study therefore suggests an important notion: the financial pressures of poverty may make poor individuals sometimes behave less pro-socially.

So they don't exclude that variance in pro-social behavior may depend on the experiment/context. Saying that this type of money-envelope experiment invalidates other/prior experiments with different setups and measures seems thus unwarranted.

And another potential issue is that the Dutch study did not consider who the poor were stealing for. Was it to feed their hungry children? Because,

again from laboratory studies, that makes a difference:

Replicating past work, social class positively predicted unethical behavior; however, this relationship was only observed when that behavior was self-beneficial. When unethical behavior was performed to benefit others, social class negatively predicted unethical behavior; lower class individuals were more likely than upper class individuals to engage in unethical behavior. Overall, social class predicts people’s tendency to behave selfishly, rather than predicting unethical behavior per se.

In other words, in laboratory experiments, there were more would-be Robin Hoods in the lower class.

And finally, it's not even the case that all laboratory experiments managed to reproduce the effect of social class (of the subject) on prosociality. There's another Dutch study (the one from which I quoted about the effect of the target class actually) that failed to replicate the effect of social class of the subject on prosociality, which may hint at the possibility of a cultural/regional effect as well. Also, another failure to replicate a direct link is noted in a UK study which proposes instead that

personal relative deprivation (PRD)—the belief that one is worse off than similar others—plays a key role in the link between social class and prosociality

They also advance some hypotheses how social class interacts with PRD, but the researchers themselves are rather reserved on those parts so I won't reproduce that here.

And probably the worst news, replication-wise comes from a PLoS one paper, which (using data mainly from Germany and the US) found mostly opposite effects

Across eight studies with large and representative international samples, we predominantly found positive effects of social class on prosociality: Higher class individuals were more likely to make a charitable donation and contribute a higher percentage of their family income to charity (32,090 >= N >= 3,957; Studies 1–3), were more likely to volunteer (37,136 >= N >= 3,964; Studies 4–6), were more helpful (N = 3,902; Study 7), and were more trusting and trustworthy in an economic game when interacting with a stranger (N = 1,421; Study 8) than lower social class individuals. Although the effects of social class varied somewhat across the kinds of prosocial behavior, countries, and measures of social class, under no condition did we find the negative effect that would have been expected on the basis of previous results reported in the psychological literature.

And one more interesting PNAS paper reports that

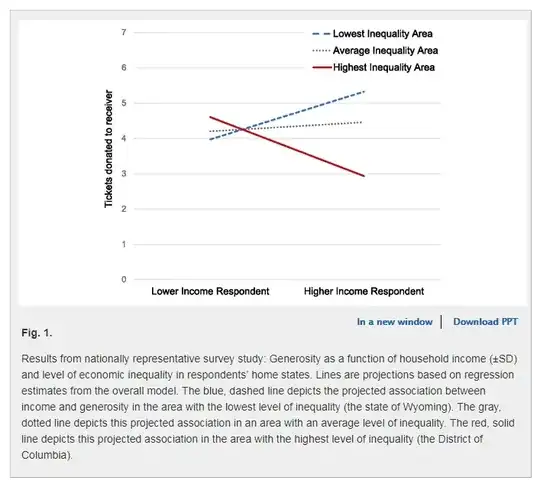

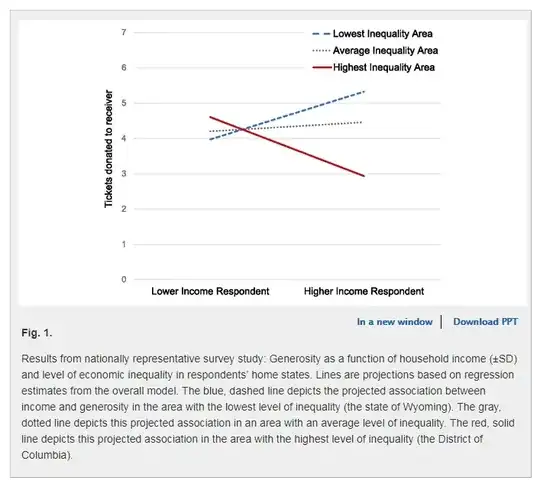

Analyzing results of a unique nationally representative survey that included a real-stakes giving opportunity (n = 1,498), we found that in the most unequal US states, higher-income respondents were less generous than lower-income respondents. In the least unequal states, however, higher-income individuals were more generous.

More research is needed, as the song goes.