A former editor of the prestigious scientific journal the BMJ has recently argued that the peer review process for scientific publications is broken and should be abandoned. He argues (my emphasis):

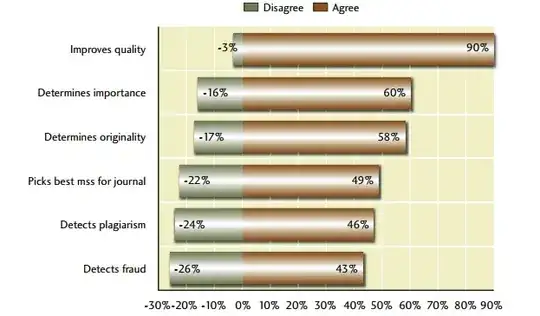

Richard Smith, who edited the BMJ between 1991 and 2004, told the Royal Society’s Future of Scholarly Scientific Communication conference on 20 April that there was no evidence that pre-publication peer review improved papers or detected errors or fraud.

Referring to John Ioannidis’ famous 2005 paper “Why most published research findings are false”, Dr Smith said “most of what is published in journals is just plain wrong or nonsense”. He added that an experiment carried out during his time at the BMJ had seen eight errors introduced into a 600-word paper that was sent out to 300 reviewers.

“No one found more than five [errors]; the median was two and 20 per cent didn’t spot any,” he said. “If peer review was a drug it would never get on the market because we have lots of evidence of its adverse effects and don’t have evidence of its benefit.”

Is he right that there is no evidence that peer review improves the quality or reduces the errors of scientific publications?

Update and clarification

I'm guilty of expressing this question is a way that missed the point it should be addressing. The current question above allows the interpretation that any improvement ever in the history of scientific publishing proves the question to be false. That wasn't my intent.

There is a serious argument (perhaps expressed too strongly by Smith) that peer review does, on balance, a rotten job. We expect it to eliminate serious statistical errors, mistakes, evidence that doesn't actually back key conclusions and other related mistakes. He argues it does a poor job at that process and that there are alternatives.

The way I hoped people might try to answer this question would be to address the question of the underlying evidence not to aim for the rhetorically satisfying hit of showing that any proof a paper was ever improved is a satisfactory answer. Smith shows that the majority of know errors are missed. He shows that most reviewers miss most errors and some miss all the errors.

What I hoped was that answers might address whether Smith's evidence is any good and whether other people have similar or contradictory evidence. That evidence will be the same whether or not we all agree on the detailed purpose of peer review. And it is an important question for this site as it puts a lot of weight on the "peer-reviewed" scientific literature.

I'm adding this as an update as I suspect that rewriting the whole question would just annoy those who have already answered.