It's complicated

There are many different ways of modelling the cost of tobacco to society, depending on what figures are included or excluded from the total amount.

For example, Devine's described model appears to have a goal of minimising only the per person cost of health care. This is self-evidently a poor choice of metric, as it justifies absurd behaviours - like letting people die quickly - or even encouraging them to die - once they get past child-bearing age.

Some of the more substantive models, such as one I will introduce below, include the costs of losses of trained workforce labour, the costs of hiring people to support the incapacitated, the cost of increased fires and even the cost of the tobacco itself (which is not spent on other industries). They consider the costs to households, businesses and governments.

This is not even include the intangibles, such as Disability-Adjusted-Life-Years (DALY) lost to smokers and the cost to their families of their early deaths.

Also different countries have different pension and health care models, so the research must be used with care.

I have only provided a selection here - the full answer could fill a book.

Finland

This study looked at 1976 men from Finland, over a period of years. The smokers has a shorter lifespan by 8.6 years. They found that, yes, this meant that smokers had a lower health care cost, and they also missed out on 7.3 years of pension.

Overall, smokers’ average net contribution to the public finance balance was €133 800 greater per individual compared with non-smokers. However, if each lost quality adjusted life year is considered to be worth €22 200, the net effect is reversed to be €70 200 (€71.600 when adjusted with propensity score) per individual in favour of non-smoking.

Conclusions Smoking was associated with a moderate decrease in healthcare costs, and a marked decrease in pension costs due to increased mortality. However, when a monetary value for life years lost was taken into account, the beneficial net effect of non-smoking to society was about €70 000 per individual.

Australia

Miranda Devine is Australian, so the Australian research is relevant.

This entire chapter does a detailed analysis of the question, based on research from 2008 and how it affected the 2004-2005 budget year. It is worth a look.

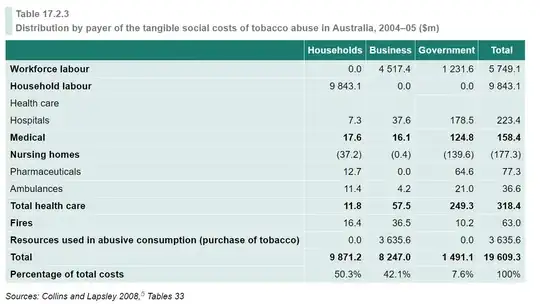

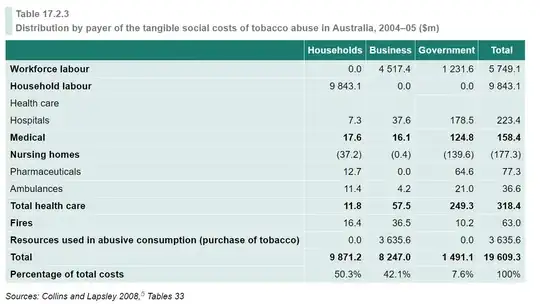

Looking at just the tangible costs, Table 17.2.3 has a column looking at the cost to the government, which appears to be Devine's concern:

It shows that, indeed, there is a saving of almost $140 million in Nursing homes, but the this is outweighed by hospital costs alone, let alone pharmaceuticals, medical and ambulance costs. In total, smoking adds $249.3 million to the costs to the government alone (and this pales compared to the overall tangibles costs, of over $19 billion.)

If you want to take taxes (both gained on tobacco products, and lost in productivity) into account, check out Tables 17.2.5 and 17.2.6. It is pretty dire.

Intangible costs to society are estimated to be about 150% of the tangible costs (Table 17.2.1), so you can see even this isn't the whole story.

Summary

Despite the complexity, Miranda Devine's comment is incorrect:

- The idea that smoking "isn't that bad" is an opinion not an empirical fact, so it isn't on-topic here.

- It shortens much more than "just a couple of years" off your life, on average (based on the Finnish data).

- It costs the Australian health system hundreds of millions of dollars more, in the long run.

- When you step back, and look at the broader picture than just the government-funded health system, the social cost is much, much worse.