CPR on Television

I don't know how many times I've seen CPR done on television where the patient immediately wakes without exhibiting any major outward signs of the effects caused by either the cause of the cardiac arrest or the CPR itself.

In the real world, this is very, very often not the case.

While there are some aspects of CPR as shown on television which are correctly portrayed, there are also some which are incorrect or at least inaccurate. Whether this is done for dramatic purposes or due to lack of knowledge on the subject is up for debate.

For the purposes of this answer, it will be much easier if we assume that all CPR done on television is done correctly.

The science...

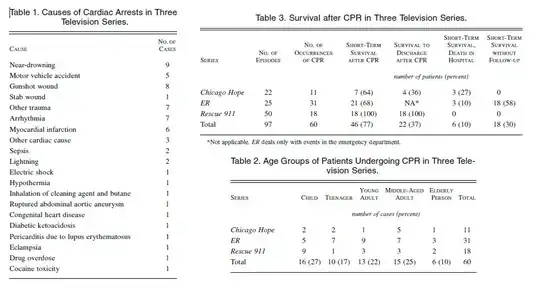

A paper studying depictions of CPR in 3 different (Rescue 911, ER, Chicago Hope) American television programs states quite clearly:

The survival rates in our study are

significantly higher than the most

optimistic survival rates in the

medical literature, and the portrayal

of CPR on television may lead the

viewing public to have an unrealistic

impression of CPR and its chances for

success. Physicians discussing the use

of CPR with patients and families

should be aware of the images of CPR

depicted on television and the

misperceptions these images may

foster.source

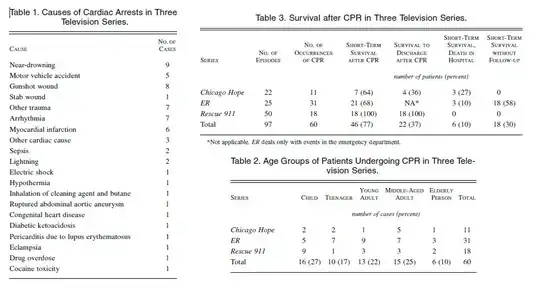

The breakdown of this study by victim is as follows:

A more recent study examined 26 episodes of Casualty, Casualty, 25 episodes of Holby City, 23 episodes of Grey's Anatomy and 14 episodes of ER screened between July 2008 and April 2009 and came to a similar conclusion.

Whilst the immediate success rate of

CPR in medical television drama does

not significantly differ from reality

the lack of depiction of poorer medium

to long term outcomes may give a

falsely high expectation to the lay

public. Equally the lay public may

perceive that the incidence and likely

success of CPR is equal across all age

groups. source

Already we can see that research indicates a sharp disparity between the effectiveness of CPR in reality and on film. Survey data cited by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation further indicates that:

The public seriously overestimates

CPR's effectiveness. A survey that

included health care workers found

that those who were over 65 years old

predicted a 59 percent survival rate

for a person treated with CPR. People

under 30 were even more optimistic,

predicting a 75 percent survival rate.

source

This data sheds light on the fact that the success rate of CPR may not only be misrepresented by the media but by the textbooks as well...

Even more troubling, the surveyors

found, was that those who had medical

training estimated CPR's effectiveness

at 75 percent! In an effort to

understand why this would be so, the

authors examined a standard text used

to train health care workers and found

only a brief acknowledgement that CPR

was unlikely to be effective. The

handbook that the Red Cross uses to

teach its CPR classes to the public

did not confront the issue of low CPR

success at all. source

CPR in the real world

Q: Does CPR alone revive people?

A: No. But it depends on if the person receiving it was actually in cardiac arrest to begin with. And what was wrong with him in the first place.

As we've already seen, the effectiveness of CPR (when done correctly) varies widely, even when combined with other therapies.

Despite the development of electrical

defibrillation and the more recent

implementation of lay rescuer

defibrillation programs, the vast

majority of these victims do not leave

the hospital alive. In studies over

the past 15 years, only 1.4% of

patients with out-of-hospital arrest

in Los Angeles, Calif, survived to

hospital discharge; in Chicago, Ill,

the number was 2%, and in Detroit,

Mich, it was <1%. Conversely, a few

municipalities such as Seattle, Wash,

report much higher survival rates from

SCA—more than 15% in 1 study—which

suggests that survival rates need not

remain so low. Recent work in Europe

and elsewhere has confirmed that a

higher survival-to-hospital discharge

rate is indeed a realistic goal, with

survival rates as high as 9% reported

in Amsterdam and 21% in Maribor,

Slovenia. source

Given the innumerable causes which can lead to cardiac arrest, I obviously cannot address them all, however, there may be some instances when CPR alone can be lifesaving, or appear to the lay rescuer that it is lifesaving.

Recent revisions of standards by the American Heart Association no longer call for lay-people to perform a pulse check prior to initiating CPR if they find an unconscious victim who appears not to be breathing. So, the person receiving the CPR may not always be in cardiac arrest.

It's possible in these situations for the painful stimuli to rouse the unconscious (usually intoxicated) person in a manner similar to what is seen on tv. To the lay person and to bystanders without medical training, this would look exactly like what is pictured on tv.

Ventricular Tachycardia, Ventricular Fibrillation vs. True Asystole

The human heart requires both electrical and mechanical activity to pump blood effectively. A patient who is pulseless and not breathing may not necessarily be "flat-lined" and in certain cases, the inititation of CPR immediately may have an effect similar to that of a precordial thump(which is now reccomended in certain situations), in that the force of the impact induces an electrical stimulus which jolts the heart out of a non-perfusing rhythm.

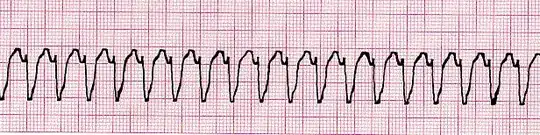

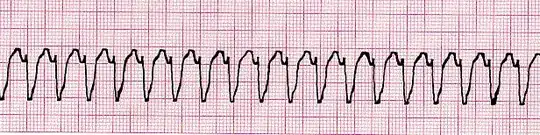

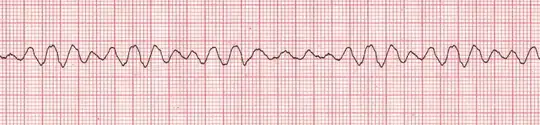

In Ventricular Tachycardia, the heart's electrical activity looks like this, but the person will often not have a pulse (because although the heart has electrical activity and some mechanical activity as well, it is inadequate to pump blood properly):

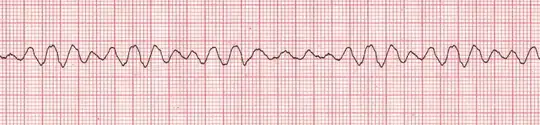

In Ventricular Fibrillation, the heart's activity looks like this, but the person will NOT have a pulse (again, because in this rhythm, the heart is unable to effectively pump):

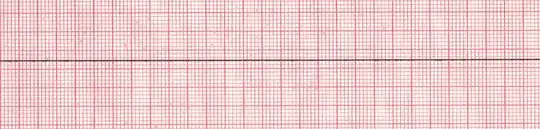

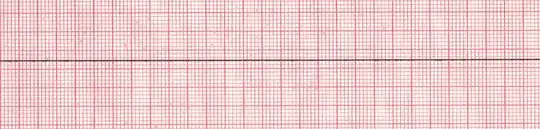

In true asystole (flatline) there is neither electrical nor mechanical activity in the heart:

However, without an EKG it is impossible to tell which rhythm a person's heart is in, and there is some chance (although probably quite remote) that the initial compression of CPR might jolt a person out of the first two, but not the third.

In reality, reversing a cardiac arrest is dependent largely on fixing the underlying cause.

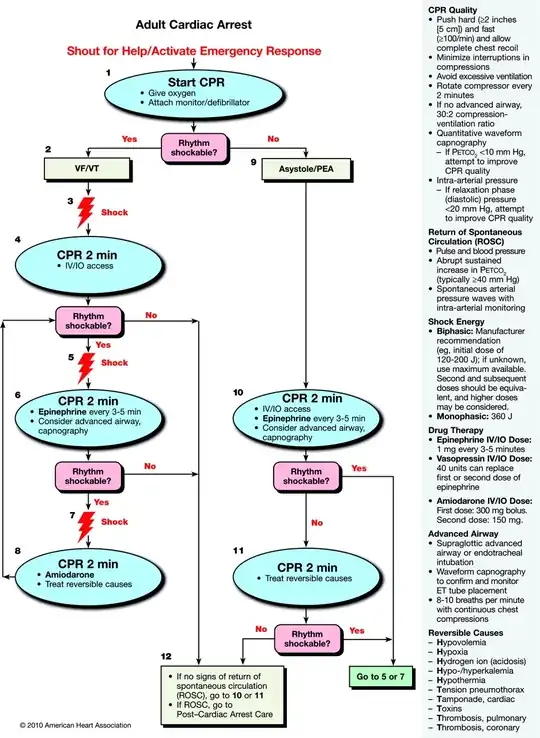

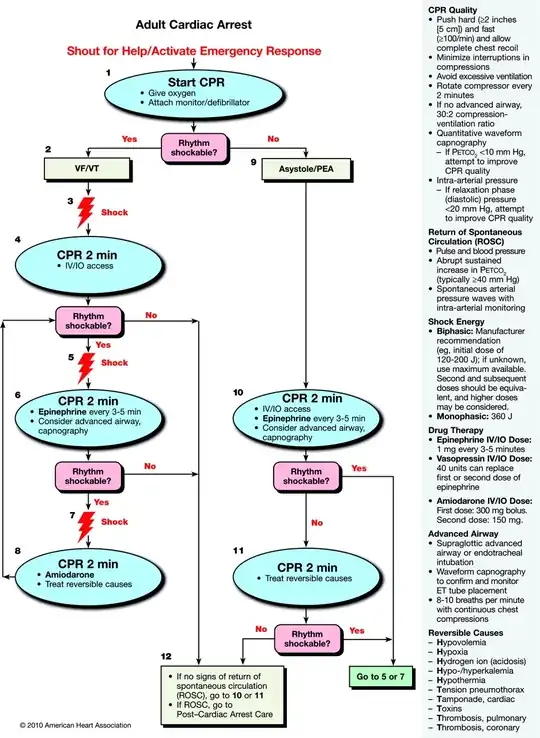

CPR is mainly effective by continuing to perfuse the body's tissues (especially the brain) with oxygen (and some other things), which will lessen damage and increase the chance of survival while other treatments (which are more effective at increasing survival rates) are administered. Typically, this involves electrical, drug, or surgical treatments. Although there are many variations, here is one example of an ACLS protocol for treating a cardiac arrest in full asystole, as you can see, it often requires much more than just CPR.

An often unaddressed factor in television is the potential for injuries caused by the CPR itself:

The most common injuries from chest

compressions are rib fracture (∼30

percent) and sternal fracture (∼20

percent). Other common

complications include aspiration,

gastric dilatation, anterior

mediastinal hemorrhage, epicardial

hematoma, hemopericardium, myocardial

contusion, pneumothorax, coronary air

embolus, hemothorax, lung contusion,

and oral and dental injuries.

The liver is the most commonly

injured intraabdominal organ, with

rupture occurring in about 2 percent

of cases. The spleen is infrequently

injured and ruptures in less than 1

percent of resuscitation attempts.

Rare injuries (incidence less than 1

percent) include tracheal injuries,

esophageal rupture, gastric rupture,

cervical spine fracture, vena caval

injury, retroperitoneal hemorrhage,

and myocardial laceration.

Complications may occur even with

properly performed CPR, especially rib

and sternal fractures. The possibility

of injury should not deter the

vigorous application of CPR, since the

outcome without effective

resuscitation is certain death.

Life-threatening injuries from CPR,

such as laceration of the heart or

great vessels, are rare. Proper

techniques will lessen the incidence

of serious complications. source

Q: Is CPR actually effective on someone who breathed water?

A: Sometimes, but not as often as television would have you think.

There is some debate about the effectiveness of rescue breathing in CPR, and in fact, lay rescuers are now taught a compressions-only method.

The role of rescue breathing is

currently debated; however, it is

likely important in prolonged arrests

or those of non-cardiac etiology.

Current recommendations encourage

inclusion of rescue breaths by trained

responders, but allow for elimination

of rescue breathing and emphasis on

chest compressions for responders

untrained or unconfident in rescue

breathing.source

A study done in a lifeguarded waterpark environment yields the following information:

Analysis of 63,800,000 guests with

56,000 rescues and 32 LSR rescues

shows that children and shallow water

both had relatively high levels of

rescues [62.6% for children aged 1-12

years and 42% for water depth less

than 1.52 m (5 ft)] and LSR rescues

[53.2% for children aged 1-12 years

and 65.6% for water depth less than

1.52 m (5 ft.)] with 87.5% of the LSR rescues resuming spontaneous

respiration and 75% having a poolside

neurological rating of Alert. source

The numbers here seem to indicate a much more impressive success rate than demonstrated above with CPR, but to understand how this works, it's important to understand the physiology of drowning.

The data appears favorable, mainly because these victims are often unconscious, but not yet in cardiac arrest. Also, the age of the patient, time spent without oxygen, and many other factors can affect survival rates.

When water enters the lungs the

victim's blood chemistry is rapidly

altered, often leading to heart

failure. In fresh water drownings

inhaled water is immediately absorbed

into the blood causing hemodilution.

The diluted blood quickly leads to

heart failure due to ventricular

fibrillation, a condition simply

described as shivering of the heart,

or anoxia (oxygen starvation). Sea or

salt water creates the opposite

effect. Water is drawn from the blood

into the lungs. This process causes

the blood to become more concentrated,

leading to an increased load on the

heart and heart failure. Older

drowning victims may experience

immediate heart failure as a result of

the initial trauma of drowning,

particularly in extremely cold

water.source

How does the drowning process happen?

A very basic outline of the drowning process:

- Panic and violent struggle to return to surface

- Period of Calmness

- Swallowing of fluid, followed by vomiting

- Terminal Gasp

- Unconsciousness

- Possible Seizures

- Death

*The time that this takes is variable, but it could be as little as 12 to 20

seconds from the first panic to unconsciousness. source

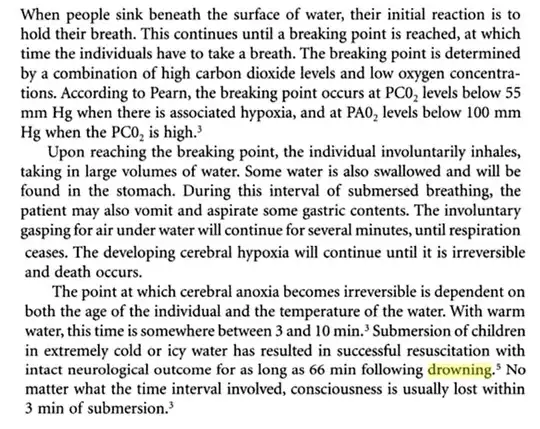

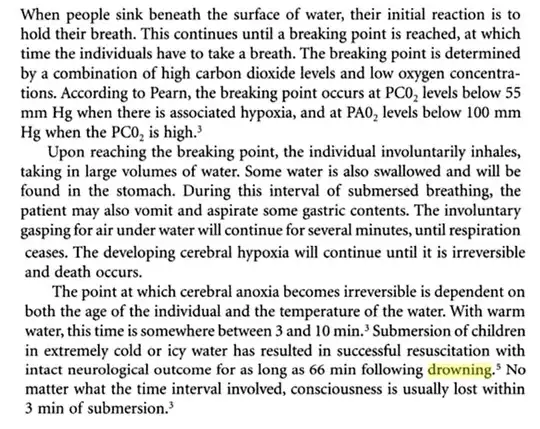

A book on forensic pathology details the process a little more delicately:

source

source

So, it could be argued that (since we have no way of knowing) some of the drowning victims portrayed in shows like Baywatch are in the very earliest stages of drowning and have only gone unconscious rather than gone into cardiac arrest, which would make their resuscitation plausible.

However, it does seem awfully convenient that they often revive their victims consistently in the most dramatic (yet, consistently vomit-free) way possible. Again, as it would seem is often the case with television and film, those telling the story tend to cherry-pick the most convenient and plot-friendly aspects of CPR.