Summary: complete colour blindness is very rare (less than 0.01%). What is common is various types of deficiency in red-green colour vision in men, which is around 8% (sex-linked because it's from an X-chromosome fault). This is based on a huge amount of evidence from accurate, widespread diagnostic testing.

You're unlikely to notice it in another person through normal social interaction because people with red-green colour blindness often learn from a young age how to estimate what's red, what's green and what's yellow/brown from contextual clues, experience, and data from other aspects of colour. It's rarely noticeable to another person outside of situations that require accurate colour identification from hue alone.

With colour vision deficiency (CVD) tests so common, there's such an abundance of data on how common it is in various groups that it's actually quite tricky to pin down one authoritative source. This quick guide to the different types is based on a table compiled in the book Colour Image and Video Enhancement by Springer press, 2015, based on Caucasian populations, which was the most completely labelled I could find. There's a huge amount of research on differences between racial groups, nationalities, occupations, etc, but from all the research I've seen there isn't any obvious pattern beyond that a distribution like this one is common:

| Type |

Male |

Female |

Complete colourblindness: "Monochromacy".

This combines monochromacy caused by having no cone cells at all ("achromatopsia"), as well as monochromacies with other causes. |

0.003% |

0.0001% |

One colour completely missing: "Dichromacy".

Functioning cone cells of one type not present in the retina: |

- |

- |

| No red: "protanopia" |

1.01% |

0.02% |

| No green: "deuteranopia" |

1.27% |

0.01% |

| No blue: "tritanopia" |

0.002% |

0.001% |

One colour shifted in sensitivity: "Anomalous trichromacy".

Causes a limited colour spectrum from one cone cell type: |

- |

- |

| Anomalous red: "protanomaly" |

1.08% |

0.03% |

| Anomalous green: "deuteranomaly" |

4.63% |

0.36% |

| Anomalous blue: "tritanomaly" |

0.0001% |

0.0001% |

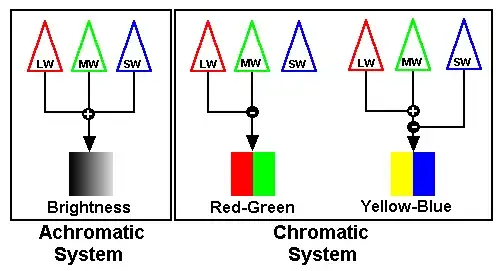

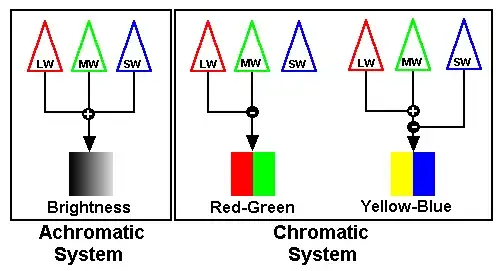

You can see the vast majority of cases are of impaired red or green vision in men. These tend to be termed "red-green colour blindness" because in practical terms, the impact is very similar. The raw data from our optic nerve is converted into "opponent processes": red opposed to green, blue opposed to yellow (where yellow is derived from the combined data of red and green cones), and light opposed to dark. Diagram from Marc Green PhD:

Whichever it is a person is less able to use, between red and green light, the main practical impact is that they are less able to discriminate red from green, but can still discriminate colours using the other opponent process between yellow (red+green) and blue.

This adds up to the widely published figures of roughly 8% of men and well below 1% of women. One example of an authoratitive source publishing this summary is the American National Eye Institute, who give the following:

As many as 8 percent of men and 0.5 percent of women with Northern European ancestry have the common form of red-green color blindness.

They go on to explain the uneven sex distribution:

Men are much more likely to be colorblind than women because the genes responsible for the most common, inherited color blindness are on the X chromosome. Males only have one X chromosome, while females have two X chromosomes. In females, a functional gene on only one of the X chromosomes is enough to compensate for the loss on the other. This kind of inheritance pattern is called X-linked, and primarily affects males. Inherited color blindness can be present at birth, begin in childhood, or not appear until the adult years.

So why aren't we constantly meeting men who can't easily discriminate red from green?

We are. It just doesn't come up in conversation.

Red and green are very different in terms of relative brightness, with reds appearing darker than greens of similar intensity. Even when someone can't tell them apart by hue, there are often other clues: a dark splatter on grass near an accident will look like blood even if its hue appears the same as the surrounding grass.

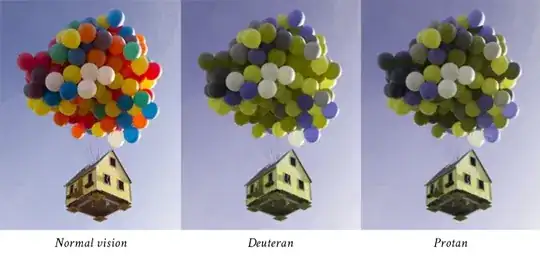

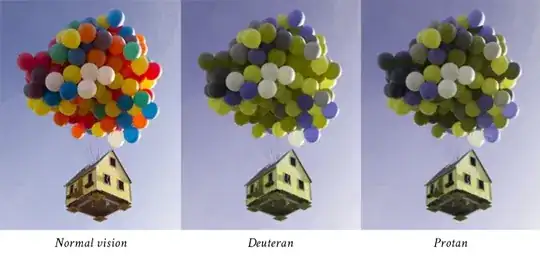

Consider this example image using simulation filters, taken from wearecolorblind.com:

It's easy to figure out how to classify the balloons in the CVD-simulated images into colourless, yellow, blue, and "other" (red, green or brown). You can even learn strategies for estimating whether a balloon is red or green (this is something that, anecdotally, colour blind people often describe doing, sometimes assuming that everyone does this; and educators point to this to explain cases where children's colour-blindness goes unnoticed - but I can't find any non-anecdotal sources for this, so I'll just leave it as an aside for now).

It's possible to tell the balloons apart, and group them by similarity. The difficulty comes in accurately naming the colours. As the author of colour-blindness.com puts it:

We are colorblind. We can’t name colors. But we can handle most situations perfectly even if we don’t know correctly which color it really is.

So, unless you habitually get in situations where you need to accurately name the colour of an unfamiliar item, there's no reason why the CVD of your male companions would necessarily become apparent.

The above linked web page gives some examples of situations where it can be a problem:

- A Sunburn can’t really be seen, only if the skin is almost glowing.

- If meat is cooked can’t be told by its color.

- There is no difference between the colors for vacant (green) and occupied (red).

- Flowers and fruits can’t be that easily spotted sometimes.

- And you can’t tell if a fruit or vegetable is ripe or not yet.

- Every electrical device which uses LED lights to indicate something is a permanent source of annoyance.

- Colored maps and graphics can sometimes be very hard to decipher.

- ...matching colors, and especially, matching clothes.