Has maternal mortality due to child birth dropped in England over the past 100 years?

Yes. Tremendously.

The 2006 paper, British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries examines this.

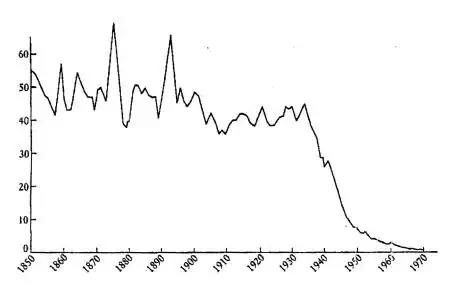

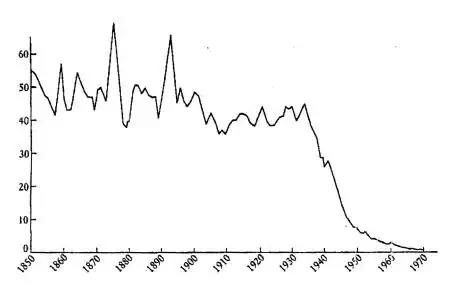

Figure 1 illustrates the incredible improvement, just up to 1970 alone.

Annual death rate per 1000 total births from maternal mortality in England and Wales (1850-1970)

We can see from the chart that, around 100 years ago, the death rate was 40 per 1000, or a 4% chance. That is, one in 25 women giving birth would die.

Does maternal mortality have a significant effect on life expectancy of women?

Yes.

The 2008 paper Life Expectancy and Human Capital Investments: Evidence From Maternal Mortality Declines looked at Sri Lanka (admittedly not England), and the improvement in maternal mortality just between 1946 and 1953. They concluded it

increased female life expectancy at age 15 by 4.1%

That is a very impressive improvement. By aged 15, girls have already passed the dangerous first years of their lives. To improve their expected lifespan by an additional 4%, from only the reduced risk of dying during child-birth gained in seven years in the mid-1900s, is almost staggering.

Are women more likely to die during later pregnancies than earlier ones?

It's not quite that simple.

The first birth is the most dangerous, and then the next few are safer. As the woman has more children, the risk grows again.

I draw this conclusion from the review paper The Relationship Between Fertility and Maternal Mortality from the book Contraceptive Use and Controlled Fertility: Health Issues for Women and Children Background Papers.

All the population-based studies indicate and results from hospital studies generally confirm that the first birth and births of high order are strong risk factors for maternal mortality (Table 2). These studies indicate a J-or U-shaped risk with parity: high during the first pregnancy, lowest during the second or third, and high again by the fifth pregnancy. A similar pattern is found for gravidity, with an even stronger relative risk for first pregnancies relative to later-order pregnancies than is observed for first births.

Notes:

Definitions:

In the UK, gravidity is defined as the number of times that a woman has been pregnant and parity is defined as the number of times that she has given birth to a fetus with a gestational age of 24 weeks or more, regardless of whether the child was born alive or was stillborn.

In the notes, the original author finds that these details of these definitions unfortunately differ between studies.

The data discussed above isn't from 100 years ago. It is largely from the 1970s and 1980s, so it might not represent the exact situation in 1915 nor 2015. This is a weakness in this part of the answer.

I don't think this section is relevant in any case, because I don't think that was what was intended by the claim, but I include it for completeness. I believe (without anyway of proving it) that the quote was probably intended to mean "Women had a life expectancy in their 40s, because they attempted to have more children than modern women, and each child-birth was riskier than today, so more of them died younger", but it was unfortunately poorly worded or poorly quoted.