In short: MDMA may have some effects, but they are likely small and reversible.

The trouble with much of the debate on the harms of MDMA is that the reporting is very biased and the underlying scientific studies are often not very good. So it isn't that difficult to find many studies the show significant harm. But this is likely a poor summary of the totality of our knowledge.

One illuminating example that resulted in major headlines and some smugness from government advisors keen on fighting the war on drugs occurred in 2002. A paper was published in the prestigious journal Science, which suggested that monkeys suffered permanent brain damage from typical recreational human doses of the drug. This looked like the first really conclusive experiment validating the idea that MDMA caused permanent brain damage. Unfortunately, the paper had to be retracted because a lab error meant the monkeys had actually been given overdoses of methamphetamine not MDMA (while chemically related, methamphetamine is a much nastier drug). That retraction didn't get anything like the headlines of the original paper.

The New York Times report on the retraction noted some other issues with Dr. George A. Ricaurte's work:

It was not the first time Dr. Ricaurte's lab was accused of using flawed studies to suggest that recreational drugs are highly dangerous. In previous years he was accused of publicizing doubtful results without checking them, and was criticized for research that contributed to a government campaign suggesting that Ecstasy made ''holes in the brain.''

The rest of the article is illuminating for discussion about the uncertainties of MDMA research.

Reviews of the effects of MDMA have been conducted in the last few years. One such review by the ACMD (the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, the scientific body intended to advise the UK government about the science of drugs) concluded that the drug was far less harmful than cocaine and heroin and should be downgraded. The government ignored this advice. Later, David Nutt, the chairman of the ACMD was sacked by the government when he (perfectly reasonably on statistical grounds) pointed out that Ecstasy was less harmful than recreational horse riding (see Nutt's book).

It is worth quoting their summary of the literature and known science. All the following quotes are from (different sections of) the ACMD report.

A concern has been raised that extensive, chronic MDMA use can lead to clinical depression, perhaps through changes in brain serotonin function discussed in Section 6. The evidence is currently equivocal – most studies do not find significantly increased levels of clinical depression in current or ex-MDMA users...

...The effects of MDMA on psychomotor function have been studied during driving performance. Studies on MDMA alone have shown that it can improve some aspects of driving and impair others (Ramaekers et al., 2006; Kuypers and Ramaekers, 2008). This contrasts with alcohol which impairs on all measures and leads to impulsively impaired judgement...

...Like amphetamines, MDMA has been found to improve impulse control and sustained attention – an effect opposite to that of alcohol...

...Early rat studies on the pharmacology of MDMA found that as well as elevating serotonin it also damaged serotonin neurons (those that release serotonin) in the brain (reviewed by Green et al., 2003). Subsequent studies in non-human primates produced similar findings (Hatzidimitriou et al., 1999), although in mice dopamine neurons were also affected. Although the doses used in these studies were considerably higher than those typically taken recreationally, these preliminary findings raise concerns that MDMA might produce similar nerve cell damage in humans.10 However, a recent non-human primate study using dosing similar to that seen in humans showed no effect (Fantegrossi et al., 2004)...

...Statistically significant alterations in some brain-imaging measures have been reported. Their magnitude is generally less than comparable findings in alcohol, cocaine and methylamphetamine misusers and the clinical relevance of these findings is unclear...

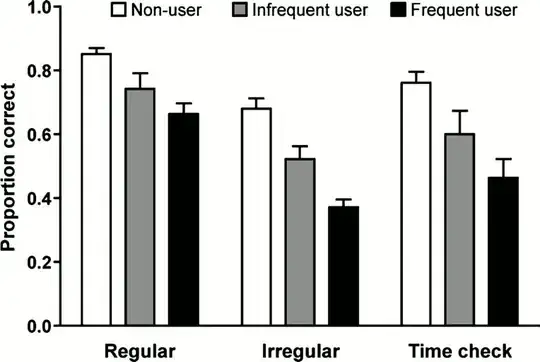

A systematic review of the literature by Rogers et. al. in 2009 (which provided some of the ACMD's evidence) concluded that there seemed to be some consistent effects but that they were small. Moreover, many of the studies were poorly conducted and may be biased. In their words:

The evidence we identified for this review provides a fairly consistent picture of deficits in neurocognitive function for ecstasy users compared to ecstasy-naïve controls. Although the effects are consistent and strong for some measures, particularly verbal and working memory, the effect sizes generally appear to be small: where single outcome measures were pooled, the mean scores of all participants tended to fall within normal ranges for the instrument in question and, where multiple measures were pooled, the estimated effect sizes were typically in the range that would be classified as ‘small’.

However, there are substantial shortcomings in the methodological quality of the studies analysed. Because none of the studies was blinded, observer or measurement bias may account for some of the apparent effect. There is a suggestion of publication bias in some analyses, and we saw clear evidence of selective reporting of outcomes.

In summary: there appear to be some effects on cognition, but they are small and there is little evidence of permanence. Moreover, some of the observations may be a result of confounding or bias.