To clarify, I see four claims you are skeptical about:

- Ancient people literally were not able to perceive the color blue.

The linked article states:

Greeks lived in a murky and muddy world,

devoid of color, mostly black and white and metallic, with

occasional flashes of red or yellow. Gladstone thought this was perhaps something unique to the Greeks, but a philologist named

Lazarus Geiger followed up on his work and noticed this was true

across cultures.

No ancient language anywhere in the world had a word for "blue".

All languages acquired a word for blue at roughly the same time

around the world

The Himba people in Namibia cannot distinguish blue from green, but

can somehow see some shades of green we cannot.

The first claim is easily falsifed. Behold the blue hippo:

This faience hippo from the Middle Kingdom Egypt (a thousands years before Homer) is not blue by accident. It is blue because it is painted with the dye Egyptian Blue. [Source: Egyptian Blue ] Since the ancient Egyptians went through the effort of manufacturing this dye and use it to paint various objects, we can conclude that not only were they able to perceive the color, they actually liked it at lot.

The dye was used from 2500 BC onward throughout the eastern Mediterranean area up to and including the Roman empire. The word coeruleum is the Latin word for the dye, and is used in first century (so classical Latin, not medieval - the formula for the dye was actually lost in the middle ages). We can conclude that the the color blue was appreciated throughout the ancient world. And why shouldn't it be? There is no indication of major physiological changes in color perception in historical times. (Color blindness presumably existed in a minority then as now, but note that the most common form is red/green color blindness, color blindness towards blue is exceedingly rare [Source]).

So where did the myth start that that the ancient couldn't see blue? It originated with the observation that Homer (the ancient Greek poet, author of the epics The Iliad and The Odysse) doesn't use color descriptions the same way that we do in modern language. He likens the sea to wine and the sky to bronze. Does this mean he was color blind and thought the sea was purple and the sky was orange? (Well, according to tradition he was actually blind, but never mind that. Most likely Homer was not a single person anyway but an oral storytelling tradition which developed over centuries.)

No, this just means the terms are used to describe the darkness/lightness rather than the hue. The sea is as dark and opaque as wine. The sky is as bright as the lustre of bronze. When you think about it, these terms are much more vivid than just saying the sea was blue, the sky was blue.

The controversial claim is that because Homer doesn't use the exact color terms we use, then he couldn't see the colors we know. This is an extreme form of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis which have been thoroughly debunked by linguists. The theory states that if a language does not have words for a concept, then the users of the language will not not be able to perceive or understand the concept.

For example many languages have distinct words for male and female cousins. English only have a single word, cousin, which covers both male and female. Does that mean English-speaking people are not able to distinguish the genders of their cousins, or are not able to fathom that cousins can have different gender? Of course not. It just makes it tricky to translate a sentence like "I have a cousin" to or from English, without cheating by adding or removing information.

The strong version Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is rejected by linguists [Source], but lives on in New-Age mythology because it playes into the "if you believe it, it is

real" philosophy which underlies much New-Age thinking. For example the New-Age pseudo-science classic "What the bleep do we know?!" used the SW hypothesis to

claim that when Spaniards arrived in the new world their ships where literally invisible to the Indians, because they did not understand what they saw. (If you follow this logic then the Americas should also have been invisible to the Spaniards.) The pseudo-science "Neuro-linguistic programming" is also to some extend based on the strong version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

Incidentally, color recognition experiments have been used to reject the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. The consensus seem to be basically that "the domain is governed mostly by physical-biological universals of human color perception" [Source] or in short: The Ancient Greeks saw blue the same way we do, whether they knew a word directly translatable to "blue" or not.

(Linguist generally does support a weaker form of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis which states that our language influence how our minds work, it just doesn't put hard limits on our abilities to perceive or understand the world.)

Regarding claim 2, this is actually contradicted by the article you link to, which states that Egyptian was the only ancient language which had a word for blue. But even this claim is wrong since we specifically know ancient Latin and Greek words for the "Egyptian blue" dye.

Regarding claim 3, this seem to be a misunderstanding of the hypothesis that languages evolve words for colors gradually and in a universal order. The claim is not that on a specific day, languages around the world invented a word for "blue", but rather that "blue" will typically be the sixth color term to appear in a language (after dark, light, red, green and yellow). This hypothesis is controversial and some counterexamples have been found, but it is not totally ridiculous. The answer by March Ho examines this in more detail.

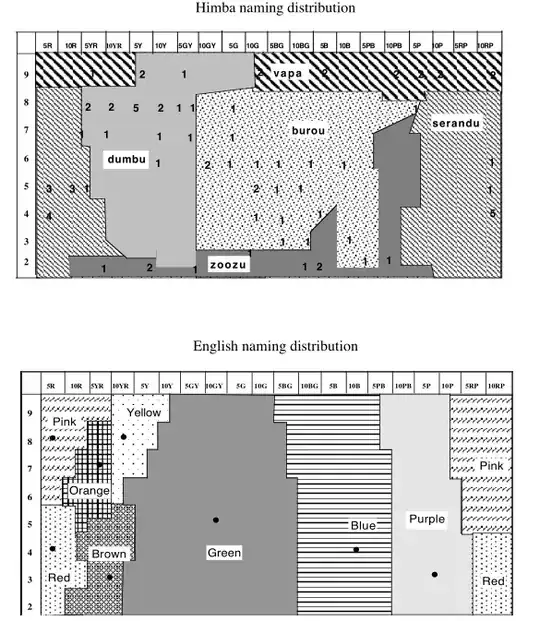

Regarding claim 4, that the Himba people not being able to distinguish between blue and green, the claim is much weaker in the wikipedia page you link to. It just states that:

"It is thought that this may increase the time it takes for the

OvaHimba to distinguish between two colours that fall under the same

Herero colour category, compared to people whose language separates

the colours into two different colour categories."

This doesn't suggest that the Himba can perceive fewer or more colors, only that the language influence how quickly we categorize colors. This points to some complex interplay between the parts of the mind that organizes the sensory experience with words and the parts that see a continuum of color shades, which is quite interesting.

Bottom line: People throughout history have been able to perceive and distinguish colors we would call blue. But they would not necessary have a word directly translatable to "blue".