GSM Association in 2013 has published white paper, which strongly suggests that there is no evidence proving any reduction in crime or terrorism.

Excerpts from summary:

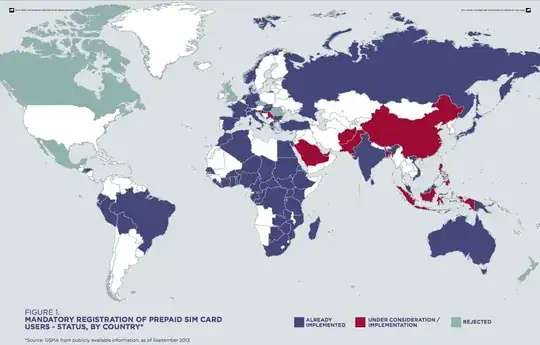

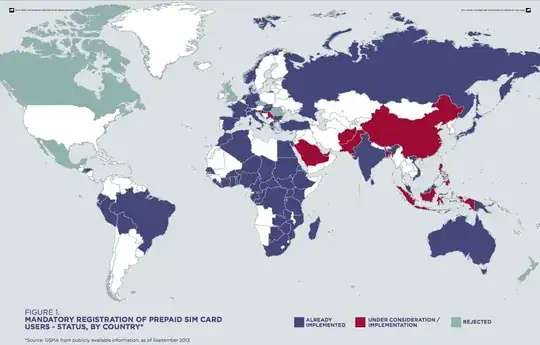

An increasing number of governments have

recently introduced mandatory registration

of prepaid SIM card users, primarily as a

tool to counter terrorism and support law

enforcement efforts. However, to date there is

no evidence that mandatory registration leads

to a reduction in crime.

A number of other governments, including

those of the United Kingdom, the Czech

Republic, Romania and New Zealand,

have considered mandating prepaid SIM

registration but concluded against it.

While these governments’ detailed policy

assessments have not been published, reports

have highlighted the absence of evidence —

in terms of providing significant benefits for

criminal investigations — as a key reason for

rejecting this policy. In Mexico, mandatory

SIM registration was introduced in 2009

and repealed three years later after a policy

assessment showed that it had not helped

with the prevention, investigation and/or

prosecution of associated crimes.

Chapter 3 of the aforementioned white paper:

While there is no doubt that criminals and

terrorists use prepaid SIM cards to help stay

anonymous and avoid easy detection, to

date there has been no empirical evidence to

indicate that:

- Mandating the registration of prepaid

SIM users leads to a reduction in criminal

activities; and

- The lack of any registration of prepaid SIM

users is linked to a greater risk of criminal or

terrorist activities.

In fact, a publicly available policy assessment

report from Mexico showed that mandatory

SIM registration—introduced there in 2009—

had failed to help the prevention, investigation

and/or prosecution of associated crimes. As

a result, policymakers decided to repeal the

regulation three years later (see case study 1).

The absence of a link between mandatory

SIM registration and crime reduction suggests

that criminals who are determined to remain

anonymous will use other means to obtain

active SIM cards or simply buy them from abroad

and roam on their own countries’ networks.

A number of governments, including in Canada,

the Czech Republic, New Zealand, Romania

and the United Kingdom have considered the

merits of mandating prepaid SIM registration but

subsequently concluded against introducing it.

In the United Kingdom for example, this issue

was considered in detail by an expert group

of law enforcement representatives, security

and intelligence agencies and communications

service providers following the terrorist attack

on London in July 2005. A confidential report

by experts concluded that “the compulsory

registration of ownership of mobile telephones

would not deliver any significant new benefits

to the investigatory process and would dilute

the effectiveness of current self-registration

schemes.”

In the European Union, some Member States

have adopted measures requiring SIM card

registration, and the European Commission (EC)

invited all Member States in 2012 to provide

evidence of the actual or potential benefit

of such measures. Following examination of

the responses, Cecilia Malmström, European

Commissioner for Home affairs noted that:

“At present there is no evidence, in terms of

benefits for criminal investigation or the smooth

functioning of the internal market, of any need

for a common EU approach in this area.”

Case study of Mexico mentioned above:

In Mexico, mandatory SIM registration was

introduced in 2009 but repealed three

years later after a policy assessment

showed that it had not helped the

prevention, investigation and prosecution of

associated crimes. The reasons cited by the

senate for repealing the regulation included:

(i) Statistics showing a 40 per cent increase

in the number of extortion calls recorded

daily and an increase of eight per cent

in the number of kidnappings between

2009 and 2010;

(ii) The appreciation that the policy was

based on the misconception that

criminals would use mobile SIM cards

registered in their names or in the name

of their accomplices. The report

suggests that registering a phone not

only fails to guarantee the accuracy of

the user’s details but it could also lead

to falsely accusing an innocent victim of

identity theft;

(iii) The acknowledgement that mobile

operators have thousands of

distributors and agents that cannot

always verify the accuracy of the

information provided by users;

(iv) Lack of incentives for registered users

to maintain the accuracy of their

records when their details change,

leading to outdated records;

(v) The likelihood that the policy

incentivised criminal activity (mobile

device theft, fraudulent registrations

or criminals sourcing unregistered SIM

cards from overseas to use in their

target market); and

(vi) The risk that registered users’ personal

information might be accessed and

used improperly.