According to the Washington Post article titled Witness 10 proves Darren Wilson had a reasonable belief he needed to shoot Michael Brown (which cites this document which claims to be a transcript of the grand jury testimony), there was an independent (i.e. other than Officer Darren Wilson) witness (named as "Witness 10") who testified that Michael Brown's hands weren't up, and that he was charging not surrendering.

Quoting the Washington Post,

He did turn, he did some sort of body gesture, I’m not sure what it was, but I know it was a body gesture. And I could say for sure he never put his hands up after he did his body gesture, he ran towards the officer full charge.

... And when he stopped, that’s when the officer ceased fire and when he ceased fired, Mike Brown started to charge once more at him. When he charged once more, the officer returned fire with, I would say, give an estimate of three to four shots. And that’s when Mike Brown finally collapsed…. (166:21-167:18).

With regard to the body gesture, Witness 10 explained: “All I know is it was not in a surrendering motion of I’m surrendering, putting my hands up or anything, I’m not sure. If it was like a shoulder shrug or him pulling his pants up, I’m not sure. I really don’t want to speculate [about] things….” (180:5). But “[i]mmediately after he [Brown] did his body gesture, he comes for force, full charge at the officer” (180:16). Ultimately, in the view of Witness 10, the officer’s life was in jeopardy when Brown charged him from close range (206:4).

See also Did Michael Brown charge?

Eyewitnesses paint a muddled picture

A since-deleted comment asked why the Washington Times might have "cherry-picked" this witness over others: Why do you believe that "witness 10" is more trustworthy than others?

To answer that question/comment, (at the risk of quoting too much of it) some reasons why the Washington Times article focuses on Witness 10 include the following:

It's sufficient (for the defence) if one reasonable person has the same belief as the defendant:

Missouri law allows a person to use deadly force defending himself when he has a “reasonable belief” he needs to use deadly force. The law goes on to define a reasonable belief as one based on “grounds that could lead a reasonable person in the same situation to the same belief.” Unsurprisingly, Officer Darren Wilson testified to the grand jury that he reasonably believed he needed to use deadly force to defend himself against Michael Brown. But the clinching argument on this point is that other reasonable people — i.e., some credible eyewitnesses — agreed with Wilson.

It would be difficult to discuss in detail the testimony of all of several dozen eyewitnesses. But a defendant raising self-defense need not show that his interpretation was the only one; rather he need only show that it was a reasonable one — i.e., a conclusion a reasonable person could reach based on all the facts.

Against that backdrop, I want to review in detail the testimony of one seemingly reasonable and neutral observer — Witness No. 10. If his objective assessment was that Officer Wilson acted appropriately, that would be strong evidence demonstrating that Wilson’s belief was reasonable.

My guess is that any so-called "strong evidence" might be enough to make an at-trial conclusion of "innocence because of reasonable doubt" almost inevitable.

Ultimately, in the view of Witness 10, the officer’s life was in jeopardy when Brown charged him from close range (206:4).

Under Missouri law, this testimony by itself (even apart from any other evidence) would have provided a sound basis for the grand jury to decline to return any charges against Wilson.

Witness 10 is not contradicted by forensics evidence:

Moreover, Witness 10′s version of the facts is quite credible. Witness 10 saw a “confrontation,” and Mike Brown’s DNA was later found inside the car. Indeed, Witness 10 was afraid that Brown might have killed the police officer inside the car when he heard the firing of a single shot. (The ballistics evidence shows two shots were fired at the car, so that is a point of difference.) Witness 10 then describes Wilson pursuing Brown but not firing any shots along the way. Here again, the ballistics tracks this testimony.

Finally, Witness 10 describes Wilson firing a series of shots as Brown charged forward. This conforms to the physical evidence showing that the bullet wounds to Brown’s body and head came from the front and that they had a downward trajectory.

Witness 10 provides independent corroboration of Officer Wilson's testimony:

Witness 10 not only gave this testimony to the grand jury under oath on Sept. 23, but also much earlier. On Monday, Aug. 11 — two days after the shooting — he gave a recorded interview to two St. Louis County Police detectives. This was before any autopsy had been completed and before the media had reported other physical evidence. Witness 10′s later grand jury testimony is consistent with the statement he gave the police just 48 hours after the shooting.

Perhaps even more important for those trying to get to the bottom of what happened is that Witness 10′s sworn testimony tracks almost perfectly the sworn testimony of Darren Wilson. For example, Witness 10 describes Wilson pursuing but not firing at Brown initially, until Brown turned and charged. Moreover, Witness 10 describes an initial series of shots, Brown stopping, Wilson stopping firing, and then Brown resuming his charge. Wilson gave the same testimony, talking about a “pause” between a first and second round of shots (vol. 5, 229:1) — only to be forced to fire by Brown’s final rush.

In sum, Witness 10 had a clear view of all the events. He gave testimony that tracked not only Officer Wilson’s testimony, but also the ballistic evidence. He gave a (recorded) statement to the police very shortly after the events. He did not know Michael Brown or Officer Wilson. And, for those who deem this important, he was reportedly an African American.

The grand jury had an opprtunity to assess the relative credibility of each witness:

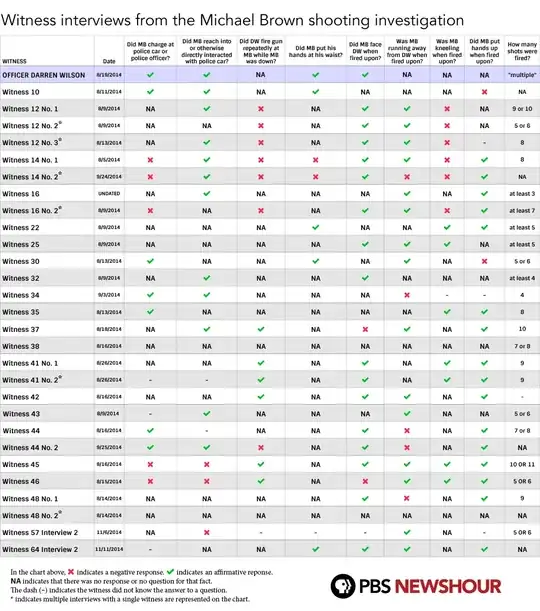

PBS acknowledged that its chart “doesn’t reveal who was right or wrong about what happened that day, but it is a clear indication that perceptions and memories can vary dramatically.” This concession is required, because a fair assessment (such as the grand jury was tasked with making) involves not simply toting up the number of witnesses on competing sides, but determining the quality of their accounts. The grand jury observed the demeanor of all of the witnesses and, perhaps even more important, had other evidence (including physical evidence) to sort out which witnesses were giving credible testimony.

The Washington Times also claims that other witnesses weren't impartial, and may for example have been subject to witness intimidation:

Why should Witness 10′s testimony be believed over other accounts? Sadly, Witness 10 gives a clear explanation about how at least some of these conflicting accounts developed. He explained that immediately after the shooting, he began

“observing the chaotic [situation], how it got so chaotic so quick[ly], and different point of views on, it didn’t add up to what I actually witnessed. I felt very uncomfortable and … I would probably estimate I was down on the scene maybe five to 10 minutes … just observing everything and how the uproar became about so quickly”(vol. 6, 190:16).

When he started saying what he had seen, some in the crowd became verbally “violent” toward him (204:3) and started directing racial slurs toward him (206:10). The next day, Witness 10 felt even more uncomfortable after he had

“seen all the rioting. I just felt bad about the situation. I knew that I needed to come forward to let the truth be told” (192:6).

And so, “after seeing the rioting,” he called St. Louis County Police:

“So I went down to the police station and I felt uncomfortable then just walking past all the protesting that was going on, but I knew it was the right thing to do. It is an unfortunate situation, but I know God put me in this situation for a reason” (192:21).

Witness 10 also spoke poignantly of trying to bring some comfort to Michael Brown’s family:

I came forward to bring closure to the family and also for the police officer because … with me knowing actually what happened … I know it is going to be a hard case and a hard thing to prove with so many people that’s saying the opposite of what I actually seen. I just wanted to bring closure to the family not thinking that hey … they got away with murdering my son. I do know that there is corruption in some police departments and I believe that this was not the case. And I just wanted to bring closure to the family (194:22).

Witness 10 also told the grand jury about a continuing concern for safety in testifying: “Within my [redacted] family … [t]hey fear for my safety or our family’s safety” (206:2).

Given the intimidation campaign that Witness 10 described, it is not surprising that PBS would find that a slight majority of the statements tracked the narrative that the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” protesters were relying on.

Some of the other witness testimony seems less reliable:

More helpful than the PBS chart is the collection of testimony from The Post. With links to the underlying grand jury testimony, a reader can click on the competing statements and read them in their entirety. But here is one overall assessment of what can be found among the testimony: “An Associated Press review of thousands of pages of grand jury documents reveals numerous examples of statements made during the shooting investigation that were inconsistent, fabricated or provably wrong. For one, the autopsies ultimately showed Brown was not struck by any bullets in his back.”

In summary,

But as I have tried to explain in this post, the issue that the grand jury ultimately had to decide was whether Officer Wilson’s assessment of the danger he faced was a reasonable one. Witness 10 was a reasonable person. He thought Wilson faced such a danger. Unless there was good reason to doubt this witness’s apparently fair-minded assessment, Officer Wilson was entitled to use deadly force in self-defense, and the grand jury plainly did the right thing in declining to indict.