I think there's a bit more recent evidence from the UK that Pigovian taxation does achieve the intended effect The UK has a £23 tax per tonne of carbon that "tops up" the £5 EU one (I'm oversimplifying that last part since the EU approach is a cap and trade scheme.) But anyway, the result in the UK:

The fresh research shows that Britain has climbed from a 2012 ranking of 20th out of 33 industrialised countries to 7th on the low-carbon electricity league table.

“Britain is reducing its carbon emissions from electricity faster than any other major country, and this has happened because the carbon price and lower gas prices have forced coal off the system – the amount of coal-fired power generation in Britain has fallen 80pc between 2012 and 2016,” said Dr Iain Staffell, from Imperial College London.

While coal generation has fallen in the UK, Dutch coal-[f]ired power plants have ramped up due to sluggish European carbon price, causing emissions in the Netherlands to rise by 40pc between 2012 to 2016.

The Dutch coal mistake is supposedly goig to be rectified by 2030, according to the latest news using the more traditional means of closing plants down, which is basically a capping scheme.

And the UK's is more or less a repeat of the Norway story (except for the exports bit):

Norway has had a carbon tax since 1991, roughly $72 per metric ton for the offshore oil and gas industry (rates vary by industry). At the same time, the country banned the practice of burning natural gas that comes up with the oil—all the CO2 for the atmosphere with none of the energy benefits—known as flaring. And, thanks to the tax, Norway hosts the world's largest CO2 storage project at its offshore Sleipner natural gas field, where millions of metric tons of CO2 have been pumped under the seafloor rather than dumped in the atmosphere. "We are by far the most carbon-efficient producer of oil and gas," says Hege Marie Norheim, senior vice president for corporate sustainability at Norway's state oil producer Statoil.

But a carbon-efficient oil and gas producer is still an oil and gas producer, which shows that a tax on carbon—even a relatively high one—is not a panacea. Since 1991 Norway has exported more than 16 billion barrels of oil. Each barrel meant 430 kilograms of CO2 entering the atmosphere when used. So Norway's oil production has added nearly eight billion metric tons of CO2 to the atmosphere when used after export to other European countries.

This is the problem of leakage: Norway's carbon tax stops at Norway's borders, unlike its oil exports.

Alas it's probably very difficult to find a comparative study of the alternatives (to Pigouvian tax) which isn't theoretical/hypothetical... you can't turn back time and most of these polluting industries have large costs so experimental economics is generally out of the question.

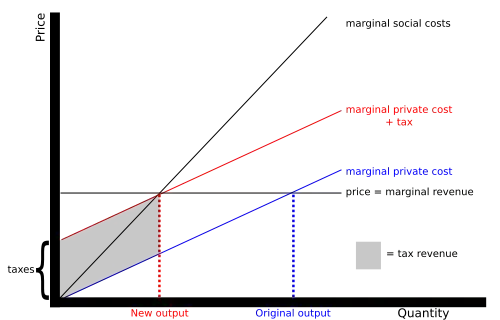

From a popsci account, Pigouvian taxes and cap-and-trade have exactly the same outcomes, but only under certain idealized circumstances. Uncertainty over the price affects cap-and-trade but not the tax system. Conversely the capping guarantees a maximum pollution level, whereas a tax system does not. Furthermore, the cap-and-trade allows "grandfathering" of industries by giving them a partially free pass initially. However cap-and-trade deprives the government of some immediate revenue. Some hybrid schemes have been proposed as well, with a price floor and/or ceiling, but these have their own problems, complexity being one obvious. (For more details on these [theoretical] comparisons, see these Berkeley course slides for instance.)

On thing that is known experimentally (and coincides with common knowledge) is that offering Pigou subsidies is better from a psychological acceptance standpoint than imposing Pigou taxes, especially under partial information. For instance when a government subsidizes clean/renewable energy, it's offering a Pigou subsidy.

There is however a subtle effect of relying only on [Pigou] subsidies for renewable energy (or in general alternatives). From a theoretical study:

Permanent renewable energy subsidies are not only an expensive choice to reduce emissions. They are also a very risky instrument because small deviations from the second-best optimum lead to strong responses in emissions and welfare. If the subsidy was set 2% below its optimal value, emissions would

increase by 18%. In contrast, if the subsidy was set 2% above its optimal value, welfare would decrease

by an additional 3% due to an over-ambitious emission reduction.

I'm not sure what changes in behavioral rather than classical economics account of externalities. I found one fairly recent study proposing that

Traditional policies to promote cooperation involve Pigouvian taxation or subsidies that make individuals internalize the externality they incur. We introduce a new approach to achieving global cooperation by localizing externalities to one's peers in a social network, thus leveraging the power of peer-pressure to regulate behavior. The mechanism relies on a joint model of externalities and peer-pressure. Surprisingly, this mechanism can require a lower budget to operate than the Pigouvian mechanism, even when accounting for the social cost of peer pressure. Even when the available budget is very low, the social mechanisms achieve greater improvement in the outcome.

It's hard to tell how something like that translates to a big scale like in a country or between countries. Uncharted waters. However countries putting political (and ultimately military) pressure on others is not unheard of... so who knows, maybe it applies.

They do mention some (obvious) caveats: like "negative peer pressure may result in retaliatory action, especially when it is perceived as illegitimate, a phenomenon that has been observed across many cultures. Thus, peer enforcement can turn prohibitively expensive if peer pressure ends in a chain reaction of retaliation." Vendettas and so forth. And a "second caveat is that the success of peer pressure relies on effective monitoring of peer action".

And in the same behavioral corner, there is a very recent experimental paper proposing that education/information is effective in producing voluntatry substituions to cleaner alternatives. They provide a quantifiable comparison between education/information and a Pigovian tax in a certain experiment involving consumer decisions in a supermarket setting. (I'll have to read it beyond its abstract to say more, and it's a pretty long paper.)