Two questions, answered with: Yes, yes and yes.

Three times yes, because there are even more factors to observe than hinted at in the question.

Modern wheat varieties have different genetics and nutritional profiles, require more fertilizer and pesticides, are planted on soils and in climates that now differ, had to adapt to different wheat disease risks.

The content of nutrients has changed concerning vitamins, secondary plant substances like polyphenols, and especially proteins, like gluten and ATI, but also fatty acids content. Some of these changes have to be seen as very beneficial. Some are not so much so good. The actual composition of what we just summarise as "gluten" has also changed.

The planting, grooming (again: fertilizers, pesticides, watering), harvesting and post-harvest processing has changed. The processing by mechanical means, bound and found but usually not measured pesticide residues, the milling.

When it comes to processing harvested wheat into products, in the industry the preference shifted ever more to that whiter meal is milled, stripping endosperm and hull, and with it vitamins, minerals and other nutrients, leaving mostly starch and proteins. This meal is then 'fortified' with chemicals to allow a even faster processing, like in baking.

These leavening agents are crucial. While the first farmers actively selected against higher protein content until the advent of leavened bread, ever since Liebig protein content was seen as the "vital force of life" nutritionally and processing wise necessary to make fluffy breads.

These protein components are 'nice to have' in a diet, but they are also responsible for the problems in celiac disease, leaky gut, and non-celiac wheat sensitivity (the more proper term for non-gluten wheat sensitivity).

Fact is that not many are really suffering from celiac disease, but a lot more experience unpleasant symptoms or even illness from eating wheat that are improving if they abstain from either wheat or gluten (from other cereals). One explanation for this is that they would tolerate isolated gluten actually quite fine in comparison, but that the gluten content is closely correlated with the content of ATI in grains. Amylase-trypsin-inhibitors are in praxis a defence mechanism of the plants and play a role in germinating the seeds. As the name implies they block enzymes.

These enzymes itself are necessary for proper protein digestion and the ATIs themselves can cause other problems throughout the body. That explains very neatly why it 'gluten-free' has much more to it than being an hysterical diet fad. Non-celiacs still suffering from a diet related illness may find relieve in avoiding gluten: both compounds are found in tandem in grains.

The desire to not let a yeast or sourdough dough rest for hours or even days is one major driver for problems. Mixing powders together and shoving it into an oven after a few minutes while still getting a chewy and tasty bread out is what industry wants and consumers accept.

But letting the microbes and yeast work on the dough makes the bread much more nutritious. The taste can be even better with synthetic chemicals. But the microbes also significantly lower the content of for example ATIs but also other things like phytic acid.

While for most ancient and heritage varieties the contents of nutrients was usually much better (easily demonstrated when just mixing einkorn and hexaploid bread wheat meal with water, einkorn giving off its much higher lutein content and turning the water yellow), the actual content of ATIs is not so easily formulated into a rule of thumb. It is not the case that all modern cultivars have just much higher content of ATIs than ancient ones. That would have been to easy and too good to be true.

With categorising wheat varieties in ancient, heritage and modern ones:

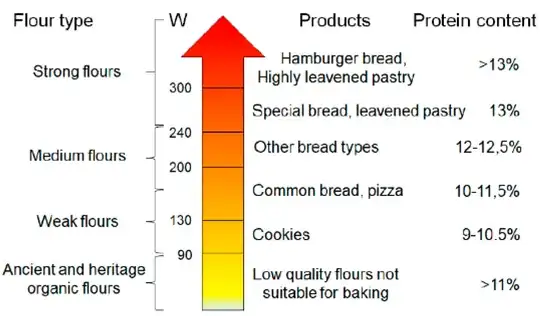

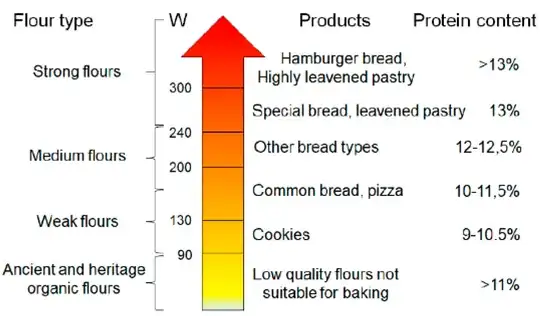

The protein and the gluten content of these wheats deserves a separate discussion. When grown today, the grains of the wild species usually have high protein contents, in the 16−28% range. It is very likely that, following domestication, the protein content of wheats has steadily declined because of the increased starch content. Since the gluten content of wheat is approximately proportional to the protein content and usually ranges between 70 and 75% of total protein content, it seems that the earliest farmers were selecting seeds for lower protein and gluten content. Only with the development of yeast-fermented (leavened) bread baking about 2000−5000 years ago, farmers may have indirectly begun to select for higher protein content because leavened bread requires a relatively high gluten content: 10–11% of protein content is considered minimal for bread making. It is possible that this selection also increased the gluten strength of wheat, measured with the modern W index (Figure 1). Wheat cultivation methods, along with selection methods, remained substantially the same until the Second World War. The wheat cultivars introduced during the last centuries before the second World War are, therefore, defined as heritage varieties, thus diversifying them from the ancient cultivars that date back to the previous millennia. In addition, heritage varieties usually have higher protein content respect to modern ones.

Flour quality, gluten strength (W), obtainable products, and protein content according to the parameters conventionally required by the food industry. Based on this classification, ancient and heritage wheat flours, obtained in organic farming, would not be suitable for baking since their W is commonly less than 90.

that this selection also increased the gluten strength of wheat, measured with the modern W index. Wheat cultivation methods, along with selection methods, remained substantially the same until the. Wheat cultivation methods, along with selection methods, remained substantially the Second World War. The wheat cultivars introduced during the last centuries before the second World same until the Second World War. The wheat cultivars introduced during the last centuries before War are, therefore, defined as heritage varieties, thus diversifying them from the ancient cultivars that the second World War are, therefore, defined as heritage varieties, thus diversifying them from the date back to the previous millennia. In addition, heritage varieties usually have higher protein content ancient cultivars that date back to the previous millennia. In addition, heritage varieties usually have respect to modern ones.

The other major characteristic, less immediate to be measured, that discriminates between heritage and modern cultivars is the strength of the gluten, with the W index passing from values below 100 to values exceeding 300, which speed up both the formation of the dough and the pasta extrusion processes and at the same time it is responsible of the typical characteristics of the current wheat products, such as the elasticity of the breads (Figure 1) or the reduced gelatinization of starches during the pasta cooking.

(–– Spisni)

Then there is another factor at play: eating patterns have changed. The role of wheat in the average diet has increased. More bread, more pasta, more pizza than ever before. Plus pretzels, cookies, sandwiches, a 'healthy" breakfast cereal of wheat pops, and even meat-ersatz based on pure gluten for the vegans…

There was and is no conspiracy out there 'to decrease the nutritional value of wheat'. All parameters available at the time the modern varieties came to market were accounted for and things improved a lot. But there are now so many unintended consequences and improved diagnostics or methods of chemical analysis to paint a much more detailed picture that is a bit more removed from triumphant march of science than some scientismists or PR people would like readers to believe. ("Like Wheat Improvement: The Truth Unveiled" By The National Wheat Improvement Committee (NWIC) PDF).

Starting from the beginning, the industrial processes that applied to wheat was the milling. Most of the modern wheat undergoes a cylinder milling, which leads to the production of refined flours of type 0 and 00 almost totally deprived of the fiber and the vitamins contained in wheat germ. On the contrary, a good part of the ancient and heritage wheats are milled in millstones and give rise to wholemeal or less refined type 1 and 2 flours. In industrial processes for bread baking, leavening powders are often used instead of natural yeasts. Natural leavening increase digestibility of wheat proteins, including gluten [49] and other proteins with potential inflammatory effects, such as amylase trypsin inhibitors (ATI), potentially reducing their immunogenic load (see Sections 5 and 6). In bakery products, vital gluten (i.e., ‘exogenous’ gluten) can be added to confer technological properties, such as emulsification, cohesiveness, viscoelasticity, gelation, and foaming. It has been calculated that the intake of vital gluten has tripled between 1977 and 2012, from 140 to more than 400 g/person/year in the USA. Finally, the higher temperature industrially adopted for fastening bread baking or pasta drying generally decreases the wheat protein digestibility. What we can say to highlight differences between products based on modern wheats and those based on ancient or heritage ones is that modern wheat are much more frequently subjected to strong industrial processes, while ancient and heritage cultivars are often processed by using more traditional methods. […]

The ancient or heritage cultivars are often stone-milled and, for the preparation of the bread, they are leavened using traditional yeasts (S. cerevisiae) or even the sourdough, very rich in lactobacilli capable of effectively degrading one of the inflammatory components of the wheat proteome: the ATI proteins [50]. Interestingly, sourdough baking seems to reduce the quantities of both ATIs and fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols (FODMAPs), short chain carbohydrates present in wheat that are poorly absorbed and contribute to intestinal bloating. On the other hand, modern grains are often refined and used for the production of processed or ultra-processed foods, with the addition of additives, such as vital gluten, which drastically worsen their nutritional values, sometimes making them fall into the worst category of the NOVA classification for processed food (NOVA 4). These industrial processes obviously do not depend on the intrinsic nutritional values of the different wheat cultivars but can certainly improve or worsen their nutritional properties.

(–– Spisni)

To be clear the cons of modern wheat varieties are there. But for non-celiac people most of the downsides they bring to the table could be mitigated to a very large degree by 1. not eating that much wheat 2. if eating wheat, preferring meal that was treated traditionally, for a longer time, with giving yest and better yet sourdough the time they need to.

More variety in choosing grains and opting specifically for either traditional or heritage cultivars from organic agriculture that are then processed by traditional means still have their valued place.

Lisa Kissing Kucek et al.: "A Grounded Guide to Gluten: How Modern Genotypes and Processing Impact Wheat Sensitivity", Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, Volume14, Issue3, pp285–302", 2015.

Enzo Spisni et al.: "Differential Physiological Responses Elicited by Ancient and Heritage Wheat Cultivars Compared to Modern Ones", Nutrients, 11(12), 2879, 2019.

Caminero et al.: "Lactobacilli Degrade Wheat Amylase Trypsin Inhibitors to Reduce Intestinal Dysfunction Induced by Immunogenic Wheat Proteins", Gastroenterology. 2019 Jun;156(8):2266-2280. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.028. Epub 2019 Feb 22.

Yvonne Junker, Detlef Schuppan et al.: "Wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors drive intestinal inflammation via activation of toll-like receptor", J Exp Med. 2012 Dec 17; 209(13): 2395–2408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102660, PMCID: PMC3526354, PMID: 23209313

Kira Ziegler, Detlef Schuppan et al.: "Nitration of Wheat Amylase Trypsin Inhibitors Increases Their Innate and Adaptive Immunostimulatory Potential in vitro", Front. Immunol., 21 January 2019

Silvio Tundo et al.: "Wheat ATI CM3, CM16 and 0.28 Allergens Produced in Pichia Pastoris Display a Different Eliciting Potential in Food Allergy to Wheat", Plants (Basel). 2018 Dec; 7(4): 101. doi: 10.3390/plants7040101 PMCID: PMC6313882, PMID: 30453594

Raymond Cooper: "Re-discovering ancient wheat varieties as functional foods", Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 2015

Detlef Schuppan & Kristin Gisbert-Schuppan: "Tägliches Brot: Krank durch Weizen, Gluten und ATI", Springer: Heidelberg, 2018.

F. Bekes et al.: "The Gluten Composition of Wheat Varieties and Genotypes PART II. COMPOSITION TABLE FOR THE HMW SUBUNITS OF

GLUTENIN (3rd edition) (PDF)

Kristin Verbeke: "Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity: What Is the Culprit?", Gastroenterology, Volume 154, Issue 3, Pages 471–473, 2018.