I know it seems like I'm carrying the "calcium" flag on this site as it seems calcium is the answer to almost any problem, but once again, if you want to be rid of dandelions, check your calcium levels:

"The lawn on the left received applications of high-calcium limestone and gypsum; the lawn on the right did not."

"The lawn on the left received applications of high-calcium limestone and gypsum; the lawn on the right did not."

Read more at: http://www.safelawns.org/blog/2010/11/guest-blog-to-reduce-weeds-and-improve-lawn-apply-calcium/

Another testimonial from a credible source can be found here: Calcium Works! Not A Single Dandelion!!!

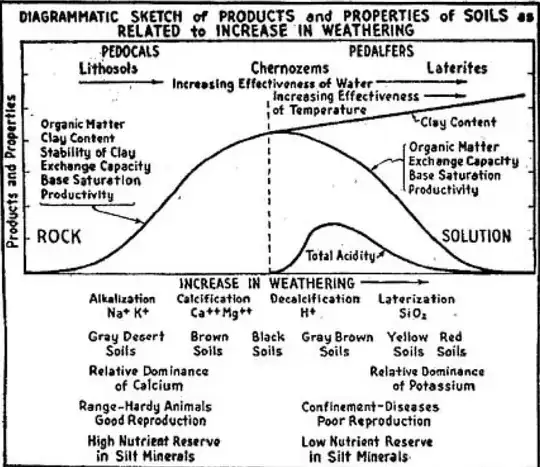

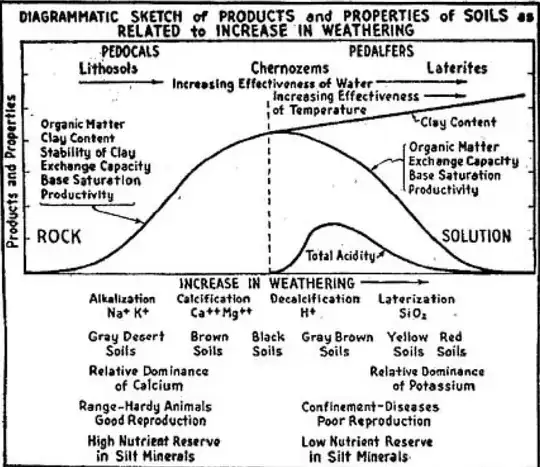

I'm a believer that each plant has its perfect soil conditions where it competes well with other plants. Clover competes well with other plants in a low-N soil. When the N levels are raised, clover doesn't compete as well as grass and the clover goes away over time. Likewise, dandelion competes in low-calcium soils. Or maybe it's better to say dandelion competes in high-potassium soils... which is really saying the same thing.

Image taken from http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010141.soil.fertility.animal.health/010106ch02.html

What this image is saying is simply when rainfall has leached calcium to the point that it is no longer the dominant mineral, then potassium becomes the dominant mineral in the soil.

Why am I bothering to tell you this?

BIOLOGICAL WEED CONTROL VIA NUTRIENT COMPETITION: POTASSIUM LIMITATION OF DANDELIONS

Weedy plants are often controlled by the application of herbicides. Here we explore an alternative method of control. We suggest that the abundance of an undesired plant species (here dandelions: Taraxacum officinale) may be controlled by modifying interspecific competition via changes in resource supply rates. This hypothesis is supported by several lines of evidence. First, analyses of effects of different patterns of fertilization on plant-species abundances in the 140-yr-old Park Grass Experiment at Rothamsted, England, show that Taraxacum abundances were highly dependent on potassium fertilization and on liming, but not on addition of other nutrients. Potassium fertilization led to a 17- to 20-fold increase in Taraxacum abundances in the classical Park Grass data, and to a 4- to 7-fold increase in the modern data. Liming led to a 2- to 3-fold increase for classical data and to a 3- to 4-fold increase for modern data.

Second, in a greenhouse study in Minnesota, Taraxacum had a higher requirement for potassium and had its biomass more limited by potassium than any of five common grass species of Park Grass. This suggests that Taraxacum may be a poorer competitor for potassium than these grasses, but this mechanism has not yet been tested. Third, in a series of Minnesota lawns that had not received fertilizer or herbicides, both Taraxacum density and abundance were significantly positively correlated with its tissue potassium levels.

This demonstration that desired and weedy plant species can differ in their resource requirements suggests that adjustments in resource supply rates may determine the outcome of interspecific competition, allowing desired species to competitively control weedy species. In particular, for soils with low potassium levels, the use of potassium-free lawn fertilizer is predicted to decrease Taraxacum because of competition from grasses like Festuca rubra.

The best way to lower potassium levels in the soil is by raising calcium levels.

Conclusion

If you raise calcium, it will dilute potassium in the soil and make it very uncomfortable for the dandelions, but the grass will love it.

Bull Thistle (source: Wikimedia commons)

Bull Thistle (source: Wikimedia commons)

"The lawn on the left received applications of high-calcium limestone and gypsum; the lawn on the right did not."

"The lawn on the left received applications of high-calcium limestone and gypsum; the lawn on the right did not."