Short answer: slow-dry the cheese under refrigeration.

Long answer:

The cheese protein matrix (casein micelles) relies on a fine balance and arrangement of milk fats finely dispersed in small globules within the protein to maintain its structure [1,2]. Heating the cheese has multiple effects - the fats flow more easily, allowing the fat globules to coalesce and break the balanced arrangement. The micelles themselves also lose their structure when heated [3,4], though some may remain intact up to 70C[1].

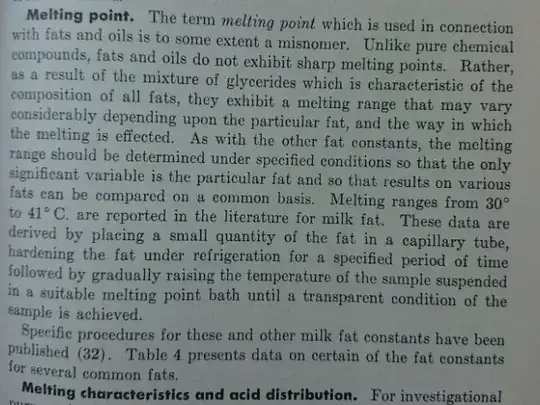

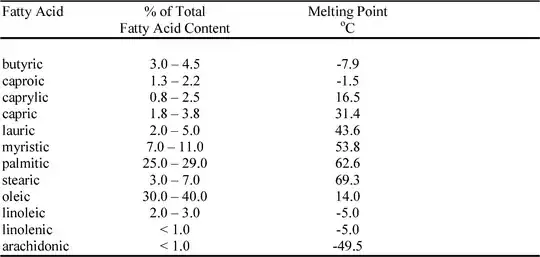

The milk fats, however, have a wide range of melting temperatures from -40C to 37C [5,6]. Some will remain liquid under refrigeration and most will be solid up to and above room temperature.

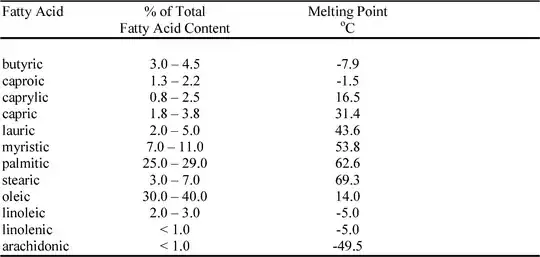

Fatty acid composition and melting points in fluid raw milk.

From Fee & Chand, Table 3 [6].

The table above highlights the major fats fatty acids in liquid milk, and will vary in cheeses.

The freeze-drying suggested by FuzzyChef relies on sublimation to remove water at or near room temperature; a more home-chef friendly option would be to simply use relative humidity gradients (drier air) to dehydrate the cheese, though much more slowly. This post and answer (work-in-progress) What is the science of drying/dehydrating meat? Biltong, jerky, etc explains the basic concepts for dehydration.

For your equipment, you can use room-temperature air at a high flow rate to dehydrate your cheese, though for food safety it's preferable to perform this under refrigeration - it's much slower, but you can increase surface area for drying by thinly slicing or coarsely grating the cheese, then grinding to your desired final particle size. More fatty acids milk fats will solidify as well, helping the casein retain its structure better during water loss.

You could also lightly dust the cheese with a neutral easily soluble starch, i.e. corn or rice, to sequester some of the fats that will be released.

Basic biology clarification regarding the table of fatty acids above:

'Milk fats' are triglycerides composed of three fatty acids attached to a glycerol chain. The melting points of the component fatty acids affect the melting point of the triglyceride as a whole, and will occur between the highest and lowest fatty acid melting points. The melting point of each fatty acid does not in itself present an 'upper limit'.

Triglycerides in milk tend to present with three different fatty acids unless one component presents at higher than 33% of the total, due to environmental or animal variation factors.

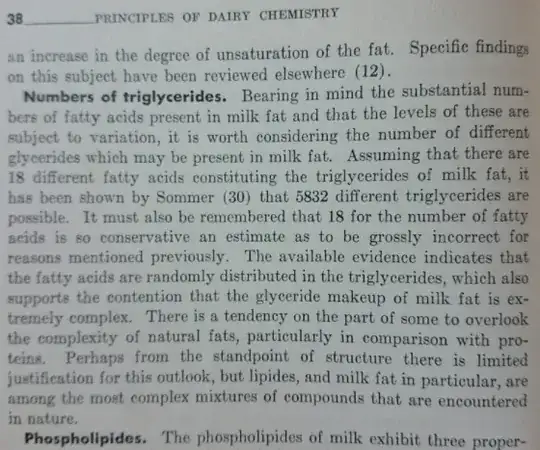

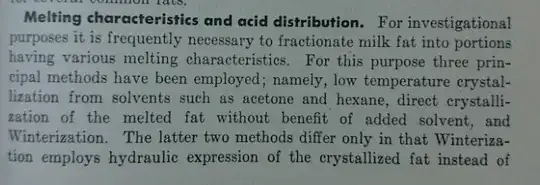

The following excerpts from Principles of Dairy Chemistry [Robert Jenness and Stuart Patton, 1959, New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1959, p38, 45-47] provide a more technical explanation and reference a complete milk fat melting point of 41C:

[1] The cheese matrix: Understanding the impact of cheese structure on aspects of cardiovascular health – A food science and a human nutrition perspective.

Emma L Feeney, Prabin Lamichhane, Jeremiah J Sheehan.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0307.12755

[1] On the Stability of Casein Micelles.

Pieter Walstra.

https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78875-3

[3] Lipids in cheese.

Michael H Tunick.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/lite.201500015

[4] Effects of Homogenitation and Proteolysis on Free Oil in Mozzarella Cheese.

Michael H. Tunick.

https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(94)77190-3

[5] Physical Properties of Milk Fat.

J.M. deMan.

https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(64)88880-9

[6] Capture of lactoferrin and lactoperoxidase from raw whole milk by cation exchange chromatography.

C. Fee, A. Chand.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEPPUR.2005.07.011